Clinicians combat the drug resistances of some cancer types by using a combination of different drugs. To make this approach more effective, chemists have designed a chemical conjugate that can simultaneously attack several cellular targets using different modes of action. Such a single-drug therapy would increase the chances of killing all cancer cells, the authors state in the journal Angewandte Chemie.

The most frequently clinically applied chemotherapeutic drug is cisplatin, a metal complex based on the platinum(II) ion. The drug’s mode of action is binding to the DNA in the tumor cells, where it distorts the DNA structure and ultimately triggers cell death. Other chemicals facilitate the interaction of cisplatin with DNA, and they are often combined with cisplatin for chemotherapy. The photodynamic therapy (PDT) approach, in contrast, relies on the activation of a metal complex by laser light. A reactive form of oxygen is formed, which interferes with cell metabolism, triggering cell death.

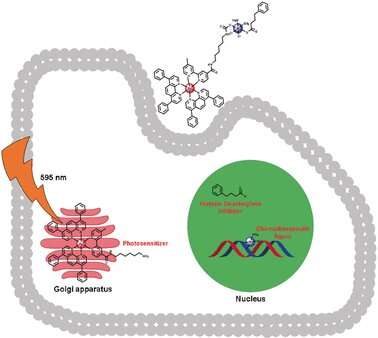

“In clinical protocols, each drug is administered separately and may not reach the tumor at the same time or at a fixed ratio,” says Prof. Gilles Gasser from the Paris Sciences & Lettres (PSL) University in Paris, France, who is one of the leading authors of the study. His group, in collaboration with Prof. Dan Gibson’s group from Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel, combined cisplatin, phenylbutyrate, which is a chemical enhancer for cisplatin, and a PDT drug, which is a metal complex based on ruthenium(II), into a single compound called Ru-Pt. The idea was that the three drugs in conjunction could travel the bloodstream intact and enter their target tumor cells, which would reduce side effects and the need to adjust the dosages.

The scientists have designed the phototherapeutic Ru(II) half of Ru-Pt so that it can be excited with laser light in the deep red section of the wavelength spectrum, which penetrates deeply in the biological tissue. The cisplatin and phenylbutyrate containing half of Ru-Pt was designed as a prodrug, which would be activated by cellular components inside the cell. Both therapeutic components were attached to each other by a molecular spacer. “The correct spacer length was critical to ensure that both drug compounds will not interfere with each other, but the molecule remains small, water-soluble, and able to travel across membranes,” Gasser says.

Source: Read Full Article