As the severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections spread rapidly over the world, causing the ongoing pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), transmission patterns have evolved quickly. At first, most infections appeared to have been imported, but by the end of February 2020, community spread was occurring in a sustained manner.

A new preprint on the medRxiv* server describes the identification of multiple circulating variants of SARS-CoV-2 during this early pandemic period from Asia and Europe. In addition, there were multiple local introductions of different variants, that resulted in multiple waves of transmission.

.jpg)

Importance of tracing mutations in SARS-CoV-2

The current study made use of whole genome phylogenetics in order to uncover the diverse genotypes in circulation in different localities. Such methods have been essential to understanding the virus's spread, identifying epicenters of infection, and for better contact tracing. The larger importance of SARS-CoV-2 diversity remains to be revealed.

It is possible that emerging mutations could confer increased virulence and transmissibility, driving the outbreak's scale. Another potential consequence could be a mutational escape from host immune responses, which has implications for vaccine development.

Study details

The researchers began with the first reported case in Philadelphia, USA, on March 10, 2020. This was just two weeks after the first case was confirmed to be non-imported and within a week of community spread in New York. Just a day earlier, the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) had begun to offer polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for the virus.

As the pandemic intensified, universal screening was initiated for all children admitted to the hospital starting April 1, 2020. These samples became the basis of the study.

The researchers examined 169 samples collected between March 19 to April 5, 2020. They carried out whole genome sequencing (WGS) on all of them. Of these samples, 83 samples were from children and young people less than 21 years old.

Extreme genomic diversity

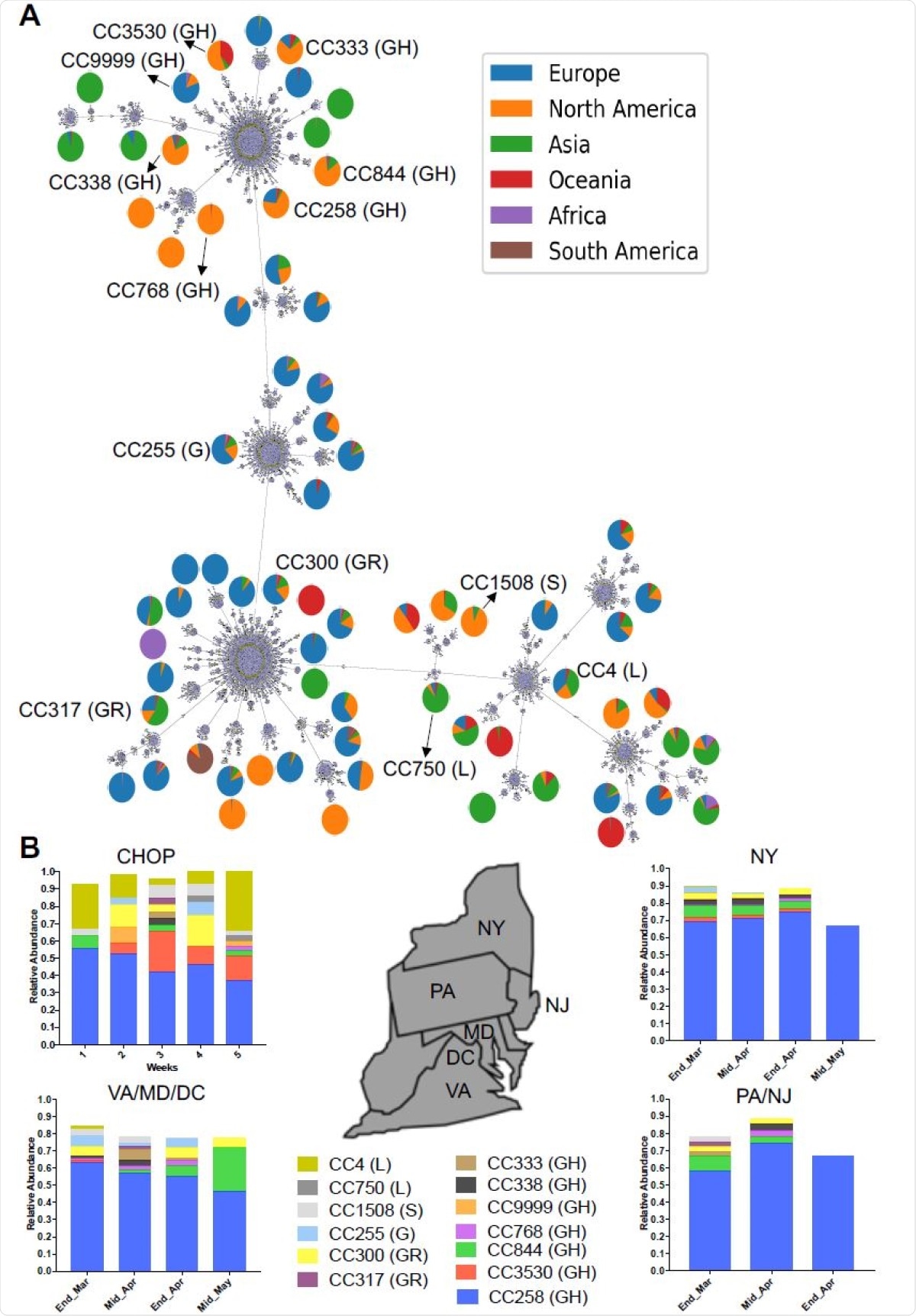

They found that this group of 169 sequences was classified into 112 sequence types (STs), with each ST sharing the same haplotype. Each ST was part of one clonal complex (CC) containing STs with only one or two different alleles from a founder sequence.

The 112 STs could be subdivided into 13 and 99 STs, respectively. The former group contained 56 genomes, and the latter had 113.

Viral genotyping was performed, and then these strains were compared with the database of global SARS-CoV-2 genomic sequences at the Global Initiative for Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID). The former STs could be precisely matched to the global database, while the latter was found to contain novel unreported alleles.

The researchers arranged the CCs by the week in which they were isolated. This showed that CC258 was persistent, but simultaneously, there were many other different haplotypes in the population.

Multiple introductions

The genomes in this small group showed extreme phylogenetic diversity, suggesting multiple introductions. To estimate this number, the researchers compared their data to high-quality GISAID sequences to locate identical STs in another geographical area 10 or more days before the date of isolation.

They found six putative introductions of independent STs. One of these had been found only in New York State previously, probably coming from that region to Philadelphia. Others were found to have been widespread, both nationally and internationally. One strain which had earlier been found only in Australia was also identified, probably an international introduction.

With an interval of five days between the identification of the strain in this location and elsewhere, three more isolates were identified, all from New York. A search for possible exportations turned up only one, to Wisconsin.

It is important to note here that these numbers (imported and exported infections) are only a pale reflection of the actual figure. They reflect only those infections that were tested and detected.

Diversity among children

The 13 CCs were found to show different prevalence patterns in adults and children. For instance, CC4, a strain that was found in Wuhan, occurred in one of five pediatric infections but in 14% of adults. Conversely, CC258 was more common in adults, at 55%, relative to children (40%).

The number of STs in CC4 was six, of which five were in children and two in adults. CC258 had many more STs at 57, of which 38 were found in adults and 25 in children.

The CC258 appears to have reached a very high peak in terms of genetic diversity in nearby New York City. This is reflected in the mutation rate for this CC, at almost 6 x 10-4 sites/year, compared to the much lower mutation rate of 2.2x 10-4 sites/year for CC4. Overall, in agreement with earlier studies, a rate of about 7×10-4 was estimated for all sequences on the GISAID database was.

Another possibility is that despite high mutation rates for both, the large population across which CC258 spread because of its higher rate of spread led to its greater diversity.

No clinical differences with genotype

The researchers found that specific clinical features were highly similar across all genotypes. Children with CC4 strains or with other strains that were circulating early in the pandemic might have had 17-fold odds of being hospitalized compared to those infected with CC258 strains or later-emerging strains.

The D614G mutation that characterizes the globally dominant variant is associated with a 90% lower risk of asymptomatic infection. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from ancestral haplotypes had significant associations with hospitalization.

What are the implications?

The current study was different from datasets from adjacent states over the same period of the pandemic, in that the range of CCs was greater, and CC4 was observed to be present, from the beginning onwards. In fact, the latter was not blotted out by the more transmissible D614G variant represented by CC258.

CC258 also appeared to have achieved continued community transmission. Further study would be necessary to pinpoint the cause of this difference, whether due to the epidemiological characteristics of the Philadelphia outbreak or the analysis of pediatric samples by themselves.

The finding of such a range of genomic mutations indicates that contact tracing could have been improved markedly by adopting WGS or similar methods to detect and group similar strains.

The early pandemic and peak in Philadelphia were characterized by multiple, diverse, circulating viral variants, especially amongst children. We also observed multiple introductions from distinct geographical origins."

The spread of the virus could be traced more accurately using WGS and genotyping tools. This could also offer opportunities to limit spread from hotspots of infection.

*Important Notice

medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

- Moustafa, A. M. et al. (2021). Early pandemic molecular diversity of SARS-CoV-2 in children. medRxiv preprint. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.17.21251960, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.17.21251960v1

Posted in: Medical Science News | Medical Research News | Miscellaneous News | Disease/Infection News | Healthcare News

Tags: Children, Coronavirus, Coronavirus Disease COVID-19, Genetic, Genome, Genomic, Genomic Sequencing, Genotyping, Hospital, Influenza, Mutation, Nucleotide, Pandemic, Phylogeny, Polymerase, Polymerase Chain Reaction, Respiratory, SARS, SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory, Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms, Vaccine, Virus, Whole Genome Sequencing

Written by

Dr. Liji Thomas

Dr. Liji Thomas is an OB-GYN, who graduated from the Government Medical College, University of Calicut, Kerala, in 2001. Liji practiced as a full-time consultant in obstetrics/gynecology in a private hospital for a few years following her graduation. She has counseled hundreds of patients facing issues from pregnancy-related problems and infertility, and has been in charge of over 2,000 deliveries, striving always to achieve a normal delivery rather than operative.

Source: Read Full Article