“I’m the boss I’m the boss I’m the boss,” says Bobby Gunn, the defending champion of bare-knuckle boxing, repeating a mantra from the film Raging Bull to himself just moments before taking the stage for the first legal, state-sanctioned gloveless fighting event in U.S. history. “Come on big fucker—let’s go.”

Walking out to Whitesnake’s “Here I Go Again” in front of a screaming sold-out crowd of 2,000 beer-drinking, cowboy-hat-wearing locals at the Cheyenne Ice and Events Center on the outskirts of Cheyenne, Wyoming, Gunn, 44, takes the stage, squaring off against his younger and larger opponent, Irineu Beato Costa, Jr., a. heavyweight boxer from Sau Paulo, Brazil. Standing just feet apart, Gunn and Costa raise their fists in a blood-stained steel circular ring built for this event, a striking image in U.S. sports history: no boxing gloves.

“Knuckle up!” one of the two referees yells.

Gunn, long used to fighting bare knuckle in underground illegal brawls with no time limits, is now forced to take a more aggressive approach in the event’s fast-paced two-minute rounds. Charging Costa, he throws a penetrating left hook to the liver, dropping him within seconds. After Costa manages a wobbly rise, Gunn then rushes him again, this time going for the kill—another deep shot to the liver topped by a final overhand right hook to the temple as he falls.

The crowd roars.

Costa lies crumpled on the ring.

The fight is over.

Bobby Gunn vs. Marcelo Tavares #BareKnuckleBoxing #BareKnuckleFC Fixed Yes or No? pic.twitter.com/MppZMxnvuk

In only 41 seconds, Gunn has proven why he is the champion of this sport, demolishing his opponent with the precision of a surgeon, the victory and body shots so quick the internet will later wonder how he did it. But for Gunn, it’s just another victory to add to his lifetime 72-0 record in bare knuckle, only this time with a crucial twist—he won in a legal arena in front of a pay-per-view audience around the world. “I thought this would get legalized,” Gunn says, smiling, the cameras flashing. “Just not in my lifetime.”

“Come on big fucker—let’s go.”

After decades of fighting in underground illegal bare-knuckle brawls from alleyways to empty warehouses across the U.S., Gunn has finally achieved a victory he never expected—defending his title in the first legal, state-sanctioned bare-knuckle fight in U.S. history. On Saturday night in an ice and roller-skating arena adorned with advertisements for construction companies and giant American flags, Gunn and 19 other fighters from pro boxing, MMA, and street brawling entered the ring to resurrect one of America’s oldest sports. The ten-card event featured a mix of up-and-coming contenders like former UFC star Bec Rawlings along with aging pros like former UFC heavyweight Ricco Rodriguez, everyone fighting in five, two-minute rounds while wearing nothing on their hands but wrapping about an inch below the knuckles.

Legalized for the first time in U.S. history by the Wyoming State Board of Mixed Martial Arts in March, bare-knuckle fighting features rules similar to pro boxing—punching only, a standard eight-count, a three-knockdown rule—but with a crucial twist: no gloves allowed. The skin on skin contact makes for a bloody spectacle. But, also, according to rising research, it likely results in a surprising benefit—fewer concussions.

“In MMA, I can grab your head and ram it against my knee,” says promoter David Feldman, a former boxer who has worked for seven years to legalize bare knuckle, getting rejected by 28 states before Wyoming finally agreed to sanction it. “How is that legal and bare knuckle isn’t? With bare knuckle, there is a perception of it being a more dangerous sport—but it’s actually safer.”

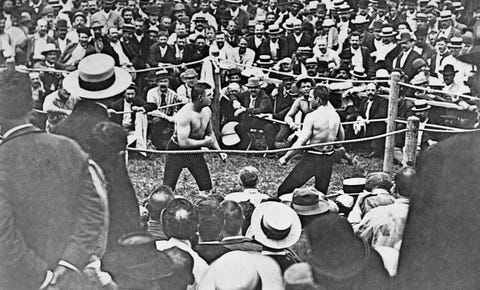

Going into the bare-knuckle event, no one really knew what would happen—the sport had not made headlines in the U.S. in over 120 years. Once one of the most popular pastimes in the U.S., bare-knuckle boxing was practiced by immigrants competing in makeshift arenas in cities like New York and Boston in the 19th century, the sport’s greatest champion, John L. Sullivan, rising from his job as a plumber to become an international star, visiting the White House at the request of Theodore Roosevelt.

But even Sullivan’s greatest bare-knuckle match—a $20,000 bout near New Orleans in 1889—was illegal, the gloveless sport covered by press but never sanctioned by a state due to its perceived brutality. In 1892, when the U.S. legalized gloved boxing as a less bloody and seemingly more civilized form of combat—the gloves resulting in less precise hits and fewer cuts—bare knuckle disappeared from the spotlight entirely.

The sport, however, never really went away. Practiced for cash in underground illegal arenas from after-hours gyms to abandoned buildings, bare knuckle has recently grown into more mainstream popularity as a possibly safer alternative to boxing. Similar to the difference between rugby and NFL football, bare-knuckle fighters hit each other with less force to keep from breaking their hands—the self-governing aspect of the sport resulting in superficial skin-on-skin cuts but seemingly fewer concussions.

“We’ve done blunt-force trauma impact studies and concussion studies,” Feldman says. “This makes sense.”

In 2008, the comeback of bare knuckle began when Gunn fought for Feldman on a pro boxing match in Arizona. Introduced to the illegal sport by Gunn—a veteran underground bare-knuckle brawler in addition to being a pro boxer—Feldman saw business potential. In 2011, he featured Gunn in a bare-knuckle boxing event sanctioned by the Yavapai Tribe at the Fort McDowell Casino in Arizona, the event held on Native American land outside of the jurisdiction of state lawmakers.

The bare-knuckle fight was expected to draw around 50,000 viewers on livestream pay-per-view, making around $500,000. Instead, it attracted so many online requests they crashed the system, leaving Feldman and the victorious Gunn with no money but a glimpse of the sport’s potential. For the next seven years, they then tried to convince lawmakers to host another event until Wyoming finally agreed to take a chance—resurrecting the sport last Saturday night to a worldwide audience.

“This is less dangerous than both sports I already oversee,” says Bryan Pedersen, chairman of the Wyoming State Board of Mixed Martial Arts. “In Wyoming, we are driven by an independent western spirit — and I’m looking to bring money to my state by taking this mainstream.”

On Saturday, the premiere of professional bare-knuckle fighting was worth the wait. In addition to Gunn’s defense of his title, the night featured an array of fast-paced fights that kept the sold-out crowd screaming on their feet, propelling the event to become a worldwide trending topic on Twitter.

Sam Shewmaker, a 33-year-old stonemason wearing U.S. flag trunks and a Duck Dynasty beard from the Ozark hills of Missouri, dropped former Bellator champion Eric Prindle in just 18 seconds with a hard right to the chin. Bec Rawlings, a 29-year-old former UFC fighter originally from Tasmania, defeated boxer Alma Garcia in the only women’s bout of the night, grabbing her in a clinch and punching her face until the refs called a stoppage following the second round.

But the night’s greatest fight was perhaps its least expected—a middle-of-the-card matchup between veteran MMA fighters Joey “the Mexicutioner” Beltran and Tony “Kryptonite” Lopez. After a slow couple of initial rounds, Beltran and Lopez—whom had twice fought each other previously in MMA events—began a blood-spattered epic back-and-forth battle, trading punches and opening cuts until finally, when the bell rang at the end of the fifth round, both men were visibly exhausted, their faces and torsos dripping in blood and sweat, Beltran ultimately declared the winner by unanimous decision.

Smiling ringside, Feldman congratulated both fighters—this was exactly the type of bout needed to generate online buzz for the fledgling sport, one that happens to be launching on the 25th anniversary of the debut of the UFC.

“Other states are reaching out to me about hosting this as well,” Feldman said, looking out across the crowd. “This is the culmination of a decade of work and it’s just incredible to see fans loving it—we’re the new combat sport in town.”

At the end of the night, after his match, Gunn sat backstage, taking off his boxing shoes and smiling. For him, the event was more than just another victory—he had finally pushed his sport from the underground to the mainstream, opening the door for a new era of fighters. Embracing younger athletes like Beltran and Maurice Jackson, Gunn gave them tips on bare knuckle maneuvers while packing his bag, the elder statesman reflecting on his own journey to this groundbreaking night. “Finally, the world is watching what we do,” he said, heading for the door. “It feels good.”

Stayton Bonner writes for Esquire, Rolling Stone, and Outside. He’s working on a book about bare-knuckle fighting due out in 2019.

From: Esquire US

Source: Read Full Article