Before he was a four-time Fittest Man on Earth, Rich Froning fell to earth.

It was 2010, his first CrossFit Games, and he was the phenom. He had a chokehold on first place heading into the final event. Then came the rope climb, and he wasn’t ready. He struggled. His legs flailed. He slipped. Then he plummeted, the sisal scorching his palms.

Froning dropped to second place, beaten by gravity. In the wake of the loss, he realized two things: First, he needed to learn how to climb that rope. That would be easy enough. He was a natural athlete with a madman work ethic.

The second problem was knottier: He knew the trophy wouldn’t always be dangling from a rope. There would be other roadblocks to success. If he was to be a champion, he needed an edge. That certain intangible something that would give him the strength to climb into the winner’s circle. He needed some juice.

#galatians614

A post shared by richfroning (@richfroning) on

So Froning did what many athletes do. He turned to the needle. The tattoo needle. Galatians 6:14. From the ninth book of the New Testament. Got it shot into his rib cage. Then he captured four CrossFit championships in a row. It’s no secret, and he’ll readily tell you so: Rich Froning got juiced with Jesus.

Take Your Struggle to a Higher Power

Fitness and faith have been workout partners for a long time.

The original Olympic Games were a religious festival to honor Zeus. In the 1850s, the phrase “muscular Christianity” was coined to represent the idea that sports helped men develop fitness, good morals, and “manly” character. The “C” in YMCA once emphatically stood for Christian. Whenever Muhammad Ali shocked the world with another victory, he gave credit to Allah. Now when athletes thank God on SportsCenter, it can seem like a cliche.

Faith can affect performance.

No one on the planet can measure faith. You can wrestle with it, but you don’t get the final score until you’re dead. Until then, hard numbers—proof that spending time with a preacher can add 10 reps to your preacher curl—are scarce. But not nonexistent. Research shows that athletic performance depends on a combination of physical skill and psychological state. For a person of faith, the two are often intertwined. It makes sense, then, that faith can affect performance.

The faithful speak of the heart and the spirit, but science points to the brain; the mental components of exercise are far more powerful than we imagined. Meditation, self-talk, mind games—it all helps.

Your decision to quit moving has both physical and psychological triggers, but the psychological ones are more malleable. Alex Hutchinson, Ph.D., author of Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance, describes it this way: “In the psychobiological model (of tolerance and intensity in exercise), effort is the yin and motivation is the yang. When you can downshift your sense of perceived effort and upshift your motivation, you can elevate your performance. Faith—and self-belief—can help you change gears.”

First let’s test faith. In a landmark study of 180 elite Korean athletes, researchers identified prayer as one of seven strategies used by high-level athletes to cope with the stress of competition. Another study, published five years later, described the use of prayer by athletes before, during, and after competition as “a common and valuable practice for enhancing performance.”

“I personally wouldn’t be where I am without my faith. I know that for a fact.”

This all makes intuitive sense. But it’s tough to keep score without real numbers. That’s what makes one 2014 study about forgiveness—a central tenet in many religions—so tantalizing. The researchers asked one group of volunteers to remember an incident in which they forgave someone who’d seriously offended them; other volunteers were asked to recall a similar incident that led to them holding a grudge. Then everyone climbed a hill. The forgivers perceived the hill to be less steep than the nonforgivers did. Of course, the key word here is “perceived.” When someone actually got out a measuring stick, the results were startling: The forgivers, after being put through what they thought was a fitness test, jumped higher than nonforgivers did.

Froning, now 30, could be living proof that forgiveness brings higher achievement—if you accept that sometimes the first person you need to forgive is yourself. He was a Christian long before he got the Galatians tattoo. But in the wake of his fall, he felt the need to recalibrate. He’d been raised in faith, but in his college years there’d been backsliding. And he was bothered by the idea that he might be worshiping CrossFit more than God. Making competition a form of idolatry. Believing that all that strength was his strength.

He began writing Bible verses about the crucifixion of Jesus on his shoes, just in case he got to thinking the clean and jerk was too tough. By focusing on Christ’s pain, Froning was reframing his own discomfort, a technique validated in a 2015 study showing that untrained participants who accepted the idea that exercise can be painful and uncomfortable actually increased their exercise time, and their perceived effort of the workouts decreased.

The Galatians ink was less a declaration of faith than a renewal of faith. So that for his every remaining earthly day, Froning might see the inscription on his skin and be at once strengthened and humbled by the words: “May I never boast except in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, through which the world is crucified to me, and I to the world.” And then he started winning.

If you really believe that improving your bodily temple, or achieving victory, glorifies God, could it not then be construed that praying to win is the right thing to do? “I don’t think I’ve ever actually prayed to win an event,” says Froning. “It’s more just, ‘Cover me.’ I’ve already put in the work. Now it’s just getting it done and not letting the nerves catch up to me. There’s a calming effect knowing that whatever happens, win or lose, everything’s going to be okay. I’ve obviously had some bad events where I thought God could help a little bit more,” he adds, trailing off into a chuckle.

Does he think the believing athlete has a competitive edge over a nonbeliever? “For sure,” says Froning. “I personally wouldn’t be where I am without my faith. I know that for a fact. So for me, yes. I’ve done things competing that I never thought were possible in training. So I can’t explain where that comes from, but I’m sure there’s somebody helping for sure.” Froning’s feelings are backed by research citing faith as an assist that helps competitors cope with stress and anxiety, attain peak performance, and provide meaning to sports participation.

There is also great power in believing that your faith and improved performance will help others. “Doing something for someone else, or working for somebody else, helps you push yourself beyond what you think is possible, or beyond what is possible just doing something for yourself,” says Froning. “My faith, my family, whatever, if you’re doing it for someone else, you’re always going to push a little bit harder.”

This thinking is backed by Italian exercise researcher Samuele Marcora, Ph.D., who studies something called motivation intensity theory, or MIT. “One of the components of MIT is potential motivation—how important it is for you to succeed in a task,” says Marcora. “Linking your success to someone getting well—especially if you believe that God can heal them—can have a very strong motivational effect.”

Find Your Own Gods

If you don’t believe in God, look for alternative kinds of faith—for instance, “a deeply felt commitment to or belief in the power of a particular routine or practice, whether it’s for health, self-improvement, or something else,” says Anne Harrington, Ph.D., a professor of behavioral science at Harvard. “The faith factor may not always need to point to some higher power. Sometimes the power of faith lies in faith itself.”

Marcora agrees, citing a U.K. study in which runners who were given fake performance enhancers improved their 3,000-meter times. “This is evidence that the belief that something can improve your performance can improve it for real,” he says. In addition to the 22 percent of Korean athletes who cited prayer as a coping strategy to help them handle the stresses of their sport, 19 percent cited superstitions—including touching their testicles—as a way to deal.

In both faith and fitness, it’s not the saying, it’s the doing.

Marcora says the stronger the belief, the stronger the effect on the outcome—and religious beliefs are among the strongest convictions that human beings have. “If you think praying or having a relationship with God improves your performance,” he says, “it becomes self-fulfilling.” (He did not weigh in on the power of pocket pool.)

With the right effort, spiritually-based fitness can work in many faiths, says Jim Lewis, Ph.D., a neuroscience researcher at Indiana Wesleyan and a chaplain in the U.S. Army Reserves. “Like physical fitness, spiritual fitness doesn’t just happen,” Lewis says. “It takes intentional effort and regular exercise in the spiritual disciplines of your tradition.”

Lewis cites resilience—the capacity to endure hardship, pain, suffering, and losing—as central to spiritual fitness. This sets up a powerful cycle: Athletes whose performances are boosted by faith also believe their faith is strengthened when it is tested; so every time they lose, they get better at winning. Athletes love that familiar saying, “That which does not kill me makes me stronger.” Lewis points out that it’s an adaptation of a quote by the famous atheist Friedrich Nietzsche, an irony that changes nothing. “It’s a framework,” says Lewis. “In both faith and fitness, it’s not the saying, it’s the doing.”

Strength Comes From Within

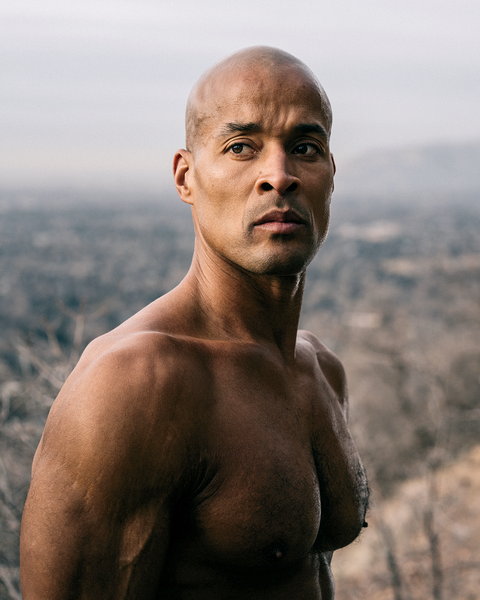

Few men do as much or are as resilient as David Goggins, a 43-year-old retired Navy SEAL. Goggins grew up in Brazil, Indiana, “a weak kid tormented by little rednecks.” His dad beat his mother, and when 6-year-old David stepped in to protect her, “he beat the courage out of me.” She left him when Goggins turned 8. As a kid he struggled through school, with a stutter and a learning disability. After high school, Goggins joined the Air Force as a tactical air controller but gained weight, maxing out at 297 pounds. His next job was in pest control, killing roaches on the graveyard shift.

We just finished the @patriottourusa where @marcusluttrell @thechadfleming @tayakyle & I get onstage & tell our stories. I tell a brief story about my childhood & how I grew up. I start talking about how my dad beat me so bad that my mom had to write letters to school explaining my absences. She would often write that I was sick but the truth was that I was so badly beaten and bruised that I couldn’t wear shorts and a t-shirt to Phys Ed, etc. I touch upon my learning disability & how I cheated on every test & homework assignment until my junior year in high school. I talk about how when I was young we moved from Buffalo to a small town in IN. In that town, there were some of the best people in the world but also some of the most racist that I have ever encountered. In 1995, the KKK marched in the town’s 4th of July parade – technically 100ft after the end of the parade. Once, during a JV bball game, the visiting crowd started chanting “Nig-ger Nig-ger Nig-ger.” After the game, I went to the visiting end to kick the shit out of some people. My JV coach stopped me & took me to the locker room. Mr. Trout sat in the locker room & cried alongside me. Like I said, while that town had a lot of good people, at 15 yo, all I could see were the racist people. I then shift to the military and all my failures and many many setbacks I had in the military. Due to the many fears I had during that time of my of my life, I gained almost 125lbs, going from 175lbs to 297lbs. I was lost & lacked self-esteem. The story moves on to getting out of the Air Force & having to lose 106lbs very quickly to try to become a SEAL. I talk about how I was in 3 Hell Weeks in 1 year, running setbacks, health issues & even discuss how my mom’s fiancé, the only father figure I ever had, was murdered. I get onstage & make light of this tragic story. I can do that becuz I faced it & overcame it. I see a shit ton of people with the victim mentality. Get over whatever is stopping you from being your best self! Rather than use the obstacles and setbacks in your life as excuses, use them as the catalyst to get better and go further in life. Don’t allow the noise of this world to cloud your thinking!

A post shared by David Goggins (@davidgoggins) on

One morning after work, a chocolate shake in one hand and a box of doughnuts in the other, Goggins slumped on the couch and turned on the TV to find a documentary on the Navy SEALs Hell Week. Goggins hadn’t been running in a year and couldn’t do five pullups, but watching the recruits “getting the shit kicked out of them” made him reflect on his life. It spurred him into action. “I was my own worst bully,” he says. “I looked in the mirror and saw a pathetic, weak, despicable person. I was not proud of anything.”

Your lies will always find you. Own your flaws, fix them.

That brutal self-assessment, a process he calls a “live autopsy,” is something he now does frequently. “You can’t hide behind the lies you tell yourself,” he says. “Your lies will always find you. If you’re fat, say you’re fat, own it, and then do something about it.” Goggins called six recruiters who laughed at him before finding one who gave him a shot. He lost the weight in three months by eating minimally—chicken breast, fruit, lots of water—and working out five times a day. He arrived at training determined to prove to himself that he was not “a pile of shit.”

“I realized that it was a mind game, me versus me,” he says. “The harder the instructors tried to break me, the harder I smiled.” His internal dialogue evolved to one of tough love. Goggins made the cut (he also passed Army Ranger training) and served 14 years with the SEALs, deploying multiple times.

After leaving the service, he used his SEAL-forged mental strength to run ultramarathons (he placed third at Badwater in 2007), an Ironman triathlon (11:24:01 in 2008), and all manner of endurance tests. He set a Guinness record for most pullups in 24 hours, raising his chin to the bar 4,030 times in 17 hours in 2013. Last year he “climbed Everest” on a VersaClimber, racing up 29,029 feet in three hours and 33 minutes. (He also did the same climb on a Jacob’s Ladder in 6:15.) Where Froning taps his faith to help him during hard times, Goggins dips into this arsenal of mental hacks.

Bust Open the Cookie Jar

The cookie jar Goggins’s virtual jar has no chocolate chips. “My cookie jar has every single failure and success of my life.” In a critical moment, he says, “I calm down, take that one second, gain control of my brain, and reach in the jar: ‘Wow, you got called nigger your whole life and you’re now the only person in history to do this, this, and this.’ Reset my mind. You have to remind yourself of how badass you are in times of need. That’s the cookie jar.”

The suck-it-up-pill

Goggins hates running: “No light feeling, my legs hurt like hell, and I hate every minute.” But he eventually learned that in order to stay mentally strong, he had to get out of his comfort zones—continuously. “I realized early in my childhood that the mind can help you overcome almost anything.” So he derives satisfaction from conquering misery. “I’m not the guy who looks at the weather report to make a decision on training. Whatever Mother Nature puts in front of me, I go out and attack it.”

The Rocky mindset

During his pullup challenge, Goggins had “Going the Distance,” from the first Rocky movie, playing on a loop. “Apollo has battered the shit out of Rocky and he walks to the corner with his arms raised, thinking Rocky is gonna quit,” he says. “Mickey is shouting. ‘Stay down,’ but Rocky climbs the ropes. You see Apollo’s face, and he’s thinking, ‘I can’t believe this guy is getting back up again.’ That’s the mindset. Go the distance. That 2 1/2-minute song powered me for 17 hours.”

The sacrifice

“I’ve participated in 50 ultra-endurance events. Some were to raise awareness and money for the Special Operations Warrior Foundation. I think about the guys who didn’t come back. They are the real heroes. They were prepared to give everything. That’s the mentality. I want to wring out every ounce of potential from my body. I believe that when you’re dead, your spirit lives on to think about all the things you didn’t accomplish in your life.”

In case you were wondering, Goggins does believe in God, although that’s not a major motivator for his fitness exploits. His endurance techniques are science-based. For the most part, says Marcora, they work because perceived exertion—a sense of effort—is what matters most in endurance exercise. “If the effort feels easy, you can go faster. If it feels hard, you stop. It may sound obvious, but it’s profound because there are lots of ways you can alter your sense of effort.” Anything you can do to distract your brain from screaming “Stop!” and reassure your body that it can handle the challenge will help you go on. The best known example is listening to music, but research by Marcora and his colleagues identifies other motivators. For example:

These are in-the-moment hacks. Other specialists are targeting mental tactics that start working further upstream.

Win the Fight Against Yourself First

Former UFC middleweight champion and current No. 3 Luke Rockhold has trained in multiple disciplines, including jiu-jitsu, judo, and Muay Thai. He travels the world to learn new training and fighting techniques—and stoke his motivation. “Anytime you spar at a new dojo, whether it’s in Japan, Brazil, or Thailand, the fighters come after the new guy,” he says. “It’s a way to test yourself against the best and to sharpen your technical skills and push yourself to be the best you can be.”

Rockhold’s motivation is not hatred for his opponents, but self-improvement. A championship bout on the calendar gives every training session urgency, and the prep follows a proven method: sparring in various disciplines, periodized strength and cardio work, and grueling mobility and core training. Like Goggins, Rockhold looks for opportunities to be in discomfort, whether it’s wrestling heavier fighters, sprinting intervals, or enduring drills like 500 high kicks on each side.

The key is not to rush or panic. You wait and wait and wait—and then strike.

Extreme drills establish deep wells of resilience. Rockhold would never execute 500 kicks in a fight, but the mind-numbing nature of the drill is partly the point. “Your goal is to kick as hard as you can each time,” says Rockhold. “The first couple of hundred, you’re focusing on form and striking explosively. But as you get exhausted, you think less about the execution and focus on your breathing. Those can be your cleanest, purest, hardest kicks.” (Plus, he’s stocking his cookie jar with performance-enhancing memories.)

Routines and drills like this serve as meditative pursuits, says sports psychologist Jonathan Fader, Ph.D. “They help the athlete tune into the moment and trust his innate talent and not overthink his performance.” Enlightened autopilot can help your performance.

Breath—or lack of it—is central to another activity Rockhold practices to toughen his mind: spearfishing. He’s been going deeper and deeper, diving hundreds of feet down to pursue cobia and staying underwater for longer than two minutes. “It’s a mental challenge because you have to relax so you’re not wasting energy. You have to be patient, efficient with your moves, and attuned to what’s happening with your body physically. The key is not to rush or panic. You wait and wait and wait—and then strike.” This self-awareness transfers to the octagon, enhancing his ability to stay calm under duress and providing a more intimate understanding and trust of his body.

Brain Training

The concept of “interoception” is a hot area of study that can sound new-agey, even spiritual. Interoception, as formally defined, consists of the receiving, processing, and integration of body-relevant signals together with external stimuli to affect goal-driven behavior. That mouthful is translated by mindfulness coach Pete Kirchmer as “a sense of what’s going on in your body—hunger, thirst, pain, temperature, heart rate, fatigue, and the wisdom to respond to it. It’s a capacity that can be trained.”

A series of brain scan studies at UC San Diego with athletes and soldiers reveals that people with heightened interoception demonstrate exceptional resilience. “It’s about using your internal awareness to anticipate and prepare for stress during extreme situations so your body doesn’t over react,” Kirchmer says. Harvard researchers found that eight weeks of mindfulness training, including meditation, decreased brain-matter density of the amygdala, the fight-or-flight center that responds to stress. Other research has found that mindfulness training can decrease the amygdala’s connectivity to the rest of the brain, reduce perceived levels of pain, and increase connectivity in brain areas associated with focus.

Kirchmer leads three-day workshops for athletes, executives, first responders, and others who are looking to perform better under stress. The cornerstones of the program are mindfulness, meditation, and movement practices designed to help participants connect with their body and focus their mind. He recommends practicing up to 30 minutes a day. Experienced meditators feel the pain, but it doesn’t trigger a stress reaction.

“Like any kind of exercise, meditation takes time to learn, and the more time you put in, the more you get out,” Kirchmer says. Start out with three to five minutes a day using a guided app such as Insight Timer or Headspace. He also teaches his clients to check in with their body before and even during a stressful activity. Take a deep breath and ask yourself questions like, “What are my feet feeling? How is my heartbeat?” Doing this can help break the trance of anxious thinking or negativity. Be observational and nonjudgmental.

Getty ImagesCaiaimage/Trevor Adeline

Negative self-talk can be effective in the short term, Kirchmer says, but a compassionate approach is more sustainable. Research by psychologist Kristin Neff, Ph.D., of the University of Texas at Austin, suggests that replacing fear of failure and inadequacy with an attitude of kindness and friendliness can fuel stronger feelings of self-belief. The goal is to treat yourself like you would if you were being a supportive, constructive coach to someone who’s learning something new. This approach emphasizes being an inner ally rather than an inner enemy in order to reach your full potential.

Ultimately you have to find the methods that best help you forge greater confidence. Everything from prayer and affirmative tattoos to activity monitors and meditation can play a role in helping you gain insights into yourself.

Then you just have to believe.

Source: Read Full Article