The gender pain gap: Why women are more likely to suffer chronic pain but are LESS likely to be taken seriously than men

- Katie Taylor was told to lose weight over back pain- she had Adenomyosis

- A hysterectomy freed Katie from the agony she had endured for years

Struck by back pain so intense she could barely walk, Katie Taylor went to her GP hoping they would investigate. Yet the only advice she got was to lose weight — even though she was, at most, half a stone overweight — and to exercise, when, despite being just 43 at the time, she could barely move around her house.

‘The pain was too bad for me to do anything,’ says Katie.

‘Simple things like going upstairs, were really difficult. I felt my pain was just being dismissed.’

Over the next four years the pain worsened, moving to her legs and joints. Katie also began to experience migraines for the first time in her life. This was on top of the agonising period pains she had quietly accepted as part of her lot as a woman for years.

Her symptoms were so bad that between the ages of 43 and 47, Katie was forced to give up three jobs in charity communications.

Katie Taylor was told to lose weight over back pain. Over the next four years the pain worsened, moving to her legs and joints. Katie also began to experience migraines for the first time in her life. This was on top of the agonising period pains she had quietly accepted as part of her lot as a woman for years. She had Adenomyosis

Her symptoms were so bad that between the ages of 43 and 47, Katie was forced to give up three jobs in charity communications. Her symptoms included heart palpitations, insomnia, anxiety and itchy skin (stock image)

Yet her GP said that Katie’s symptoms, which by then also included heart palpitations, insomnia, anxiety and itchy skin, were all in her head.

‘I was made to feel like a hypochondriac,’ says Katie, now 53, from North London, a mother of four and CEO of an online platform for midlife women.

‘I was told there was no physical cause, that the symptoms were in my head as I may have depression. They wanted to put me on anti-depressants. But I felt I wasn’t being listened to.’

It took four years after her initial visit to the doctor to get to the root cause of her joint pain and other symptoms — and this only happened after her concerned father, a breast surgeon, suggested she see a private gynaecologist.

A blood test revealed Katie was in perimenopause (the lead-up to the menopause) and her oestrogen levels were very low.

As the hormone protects joints and reduces inflammation, low levels can lead to joint pain and her other symptoms, such as heart palpitations and brain fog.

Katie was prescribed HRT (hormone replacement therapy) ‘and within just four weeks most of the symptoms went away — my husband said he heard me laugh for the first time in four years,’ she says.

But she still had crippling period pains. Further tests revealed the ‘heavy periods’ that Katie had endured for decades were due to adenomyosis, a little-known condition despite it affecting one in ten women, where endometrial tissue that normally lines the womb grows in the muscle wall and breaks down and bleeds each month. This causes sharp pelvic pain and heavy bleeding.

Adenomyosis is usually treated with anti-inflammatory medication for the pain; hormone therapy to help control heavy or painful periods; and in extreme cases by a hysterectomy

Previous attempts to seek medical help for her period pain had resulted in Katie feeling ‘dismissed’ and the impression that her period was no ‘worse than anyone else’s’, she says.

By the time this was diagnosed, just before her 50th birthday, Katie needed a full hysterectomy, i.e. removal of the womb and ovaries.

Adenomyosis is usually treated with anti-inflammatory medication for the pain; hormone therapy to help control heavy or painful periods; and in extreme cases by a hysterectomy.

It was a major operation but freed Katie from the agony she had endured for years. The question is why would so many health professionals be so dismissive of a woman’s pain and for so long?

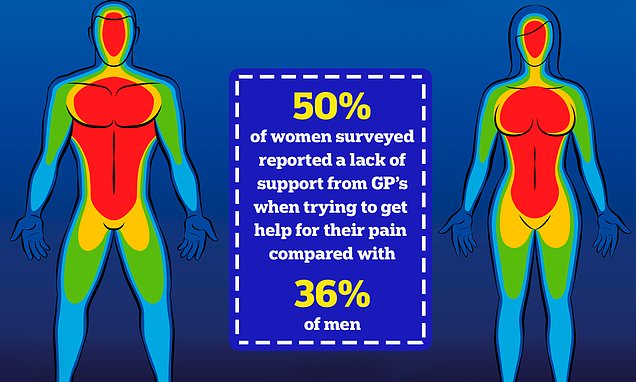

According to a recent survey, it’s a common problem. The survey of more than 5,000 men and women aged 18 to 65 about their experiences and perceptions of pain found a noticeable disparity: half of the women surveyed (50 per cent) reported a lack of support from their GPs when trying to get help for their pain, compared with 36 per cent of men, according to the results of The Gender Pain Gap Index Report, published last November by Reckitt Benckiser, which manufactures painkillers such as Nurofen.

Nearly two-thirds (63 per cent) of women said they felt men’s pain is taken more seriously owing to ‘gender discrimination by healthcare professionals’.

More than half (56 per cent) of women felt ignored or dismissed as ‘emotional’, compared with 49 per cent of men surveyed.

And the problems weren’t isolated to their treatment by healthcare professionals — one in four women (24 per cent) said generally no one took their pain seriously compared with one in six men (17 per cent). This replicates previous findings showing a difference in the way women seeking help for their pain are treated.

The term ‘gender pain gap’ was coined by Diane Hoffman, a professor of law at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, U.S., to sum up the findings of her research, published in the Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics in 2001.

It highlighted an imbalance in the treatment of pain between men and women, showing that although women were more likely to report chronic pain from conditions such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia and migraine, they were less likely to be adequately treated by healthcare providers than men.

Professor Hoffman, who last year published a follow-up article in the same journal, says that two decades on from her original research, little has changed.

‘There was a lot of attention when we published the first paper and as there’s more awareness of diversity and disparity generally I hoped there would have been more change,’ she told Good Health.

‘However, Yentl syndrome [where women are misdiagnosed and poorly treated unless their symptoms or diseases conform to that of men] still exists and women are still treated less effectively than men in their initial encounters in the healthcare system, having to prove that they are as sick as male patients.’

By way of example, she points to a study that showed after a heart bypass graft women are often given sedatives as they are perceived to be anxious, while men are given more appropriate and stronger pain relief.

This was published in 1990 in the journal Sex Roles, but Professor Hoffman says the findings remain true for today.

‘I think treatment of women for pain may have improved in the past 20 years in some institutions where it was made a priority but there are still many places where it is a problem and there is still disparity in the way women and men are treated.’

Professor Hoffman is concerned about the bias that she says remains in medical schools.

A 2015 study, published in the journal Pain Medicine, in which medical trainees were shown avatars with the same symptoms — only their sex was different — had worrying findings.

‘A third of the trainees had stereotypical attitudes that women’s pain has less of an impact on their work, and that antidepressants and counselling were appropriate treatments — yet again a woman’s pain was seen to be psychological, and that’s troubling,’ she says.

Professor Hoffman also found multiple other examples of bias during research for her 2022 paper — there were similar results to the 2015 study in two previous studies, published in 2013 and 2014 (in The European Journal of Pain and the Journal of Pain respectively), using virtual patients to assess the reaction of healthcare providers.

‘The studies found that females were significantly more likely to receive recommendations for antidepressant and psychological treatment than males, despite having similar symptoms and pain facial expressions,’ she says.

‘In those same studies, men were more likely to be prescribed analgesics than women.’

The gender pain gap is a recognised problem. Researchers writing in the Scandinavian Journal of Public Health in 2022 called it ‘a public health concern’ and said it ‘should be considered in any future pain prevention and management strategies going forward’.

They came to that conclusion after examining data from nearly 28,000 men and women aged 25 to 74 in 19 European countries — including the UK. This is despite the fact that women are more likely to live with chronic pain (defined as lasting longer than three months) in all age groups.

A report by the charity Versus Arthritis in 2021 found that among the 16 to 34 age group 22 per cent of women had chronic pain compared with 13 per cent of men.

In the 35 to 44 age group the figures were 33 per cent of women and 25 per cent of men; and in the older 45 to 54 years age group they were 41 per cent of women and 37 per cent of men. This report also found that 14 per cent of women have severe pain compared with 9 per cent of men — again, a disparity consistent in all ages.

One of the reasons for this, says Dr Franziska Denk, a senior lecturer in pain biology at King’s College London, is that autoimmune diseases such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis are more common in women, who have a stronger immune response.

As these are painful diseases, it partly explains why more women than men live with chronic pain.

Yet while they experience more pain, there is a recognised gender bias in clinical trials generally, including pain.

‘In the past, pre-clinical [i.e. animal] studies were mostly done on male mice,’ says Franziska Denk.

A report by the charity Versus Arthritis in 2021 found that among the 16 to 34 age group 22 per cent of women had chronic pain compared with 13 per cent of men

‘As female mice had menstrual cycles, it was thought they would be unpredictable and cause more variation in the results — although there is no evidence to support this view.’

Another factor often overlooked by researchers, says Dr Sarah Love-Jones, a consultant in pain medicine at Southmead Hospital Bristol, is that women’s responses to pain differ from men’s. ‘There are many contributing factors, one being that female hormones can affect the receptors in the nervous system, which affects pain transmission and causes differences in the pain processes in the brain between men and women,’ she says.

This can have a significant clinical impact, she says, pointing to a 2000 study in the New England Journal of Medicine that found that women are seven times more likely to be misdiagnosed and discharged in the middle of a heart attack. ‘This is often because women don’t have the classic chest and arm pain symptoms that are common in men,’ she says.

‘A lot of the concepts of most diseases are based on an understanding of male physiology, with 80 per cent of research studies conducted on male mice and human men.’

One of the things needed to improve the treatment of women in pain is to address the stereotypes, and not just from the doctor’s point of view, says Dr Elinor Cleghorn, a freelance researcher specialising in the history of women’s health, based in Sussex, and author of Unwell Women: A Journey Through Medicine And Myth In A Man-Made World. ‘A lot of these biases are fed by prejudices of what we think when a woman says, “I am in pain”. There’s long been an inherent assumption that women’s pain is related to their mind and emotions, not their body.’

What’s more, she adds, the view that women can cope with high levels of pain is a myth. ‘The truth is pain tolerance is subjective and varies between people,’ she says.Her research was prompted by her experiences after she developed joint pain and swelling that was exacerbated by sunlight.

‘In the hot summer of 2003 I felt I was swollen and full of pain,’ she says. ‘Some days I couldn’t get out of bed, but my doctor said I was probably stressed — at the time I was a university student.

‘I was made to feel like an anxious hypochondriac so I didn’t push for complex blood tests. It wasn’t until eight years later, when I was pregnant with my second son, that it was discovered I actually had the autoimmune disease lupus.’

Lupus causes the immune system to attack healthy tissue, triggering swelling and pain; 90 per cent of those affected are women.

The outlook, however, is looking more hopeful. Franziska Denk says pain research is now being taken more seriously in the UK. She is a member of the government-funded Advanced Pain Discovery Platform on Visceral Pain, which is looking to identify if there is a common cause of the pain experienced in conditions affecting the bladder and bowel in men and women and, in women, the uterus.

Meanwhile, in the U.S. the Society for Women’s Health Research is dedicated to promoting research on differences in disease and improving women’s health through science, policy and education. It has been vocal about the need for equality in the development of new medicines, reporting in 2017 that for the first time women accounted for more than half of research participants for drugs approved by the U.S. regulator, the Food and Drug Administration.

The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry says in the UK there is guidance to encourage diversity in clinical trials. Following its survey, the manufacturer of Nurofen has said future trials will consist of equal numbers of men and women.

‘For four years I wasn’t functioning properly, often spending days asleep on the couch,’ Katie says. ‘This shouldn’t be the case — our pains and symptoms must be taken seriously’

Professor Kamila Hawthorne, chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP), said: ‘It’s clear from these survey results that a significant number of women do not feel as though they have been taken seriously by the NHS and it’s important this is recognised and addressed.

‘Women’s health is a priority for the RCGP and we’ve worked with partners, including the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare to develop educational resources to support healthcare professionals deliver the best possible care to women.’

In the meantime, while there may not be a cure for their pain, proper support can help women and men have a better life.

Dr Love-Jones says this won’t necessarily mean medication.

‘The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines say to offer cognitive behaviour therapy for managing the effects pain has on patients’ lives, and both men and women can receive this if they’re treated at a pain clinic,’ she says.

In fact, research, such as a 2018 study in the journal Medicine, has found that women benefit more than men from this kind of approach.

Katie Taylor says that, while this is welcome news, for too many women this comes too late after years of unnecessary suffering.

‘For four years I wasn’t functioning properly, often spending days asleep on the couch,’ she says. ‘This shouldn’t be the case — our pains and symptoms must be taken seriously.’

- How long did it take to get the cause of your chronic pain diagnosed? Tell us your story: email [email protected]

Source: Read Full Article