All biological cells are bounded by a lipid bilayer known as the plasma membrane. In addition, the cells of higher organisms contain specialized intracellular membrane compartments, which interact with each other and with the plasma membrane. The highly dynamic functional interplay between these membrane systems plays a vital role in many biological processes, and is essential for normal cell function and survival. A new report published by a group of researchers led by Christoph Klein (Professor of Pediatrics at Dr. von Hauner’s Children’s Hospital, which is part of the LMU Medical Center) throws new light on the action of a key component of this network, and uncovers its significance for the development and function of human T cells. The new findings appear in the online journal Nature Communications.

Klein’s research focuses on rare genetic diseases that manifest at an early age and whose etiology is unknown. Nowadays, the first step toward an understanding of such a disorder is the identification of the genetic mutations responsible for the condition. “In the case that concerns us here, we were able to identify mutations in one specific gene in a cohort of 10 patients identified by the global Care-for-Rare Alliance, which I initiated some years ago. This gene codes for a key protein called FCHO1, which is found at the plasma membrane,” Klein explains. “In all, we discovered six different mutations in this gene, each of which interferes with the protein’s normal function.” All of the children affected suffer from severe, life-threatening immune deficiencies associated with defective T-cell function. These genetic studies implied that FCHO1 is involved in an essential biological process.

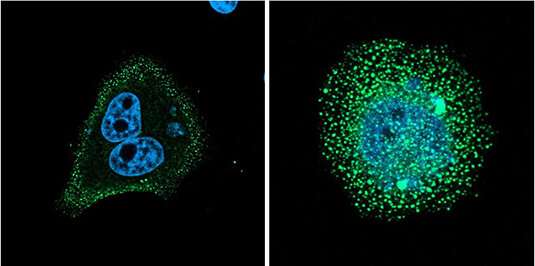

This inference is supported by the earlier finding that FCHO1 acts at an early stage in the process of clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME). CME is responsible for the uptake of fluids and the retrieval of proteins from the cell membrane, at sites that are marked by binding of the protein clathrin to its inner surface. This interaction triggers the involution of a membrane patch to form a clathrin-coated pit, which then rounds up and pinches off to yield a ‘coated vesicle.’ The mutations in FCHO1 might therefore be expected to disrupt this process, which could in turn account for the immune deficiency observed in the affected children. To test this hypothesis, Marcin Łyszkiewicz and Natalia Ziętara—joint first authors of the study—set out to characterize the consequences of the different mutations for the biological role of FCHO1 under defined experimental conditions. Indeed, their results demonstrated that the six mutations resulted in the mislocalization of FCHO1 or otherwise interfered with its ability to interact with its normal binding partners. These findings therefore imply that the immunological defects observed in the patient cohort can be attributed to a failure to initiate endocytosis at the plasma membrane.

To investigate the impact of the loss of FCHO1 at the cellular level, Łyszkiewicz and colleagues deleted the gene in a cultured T-cell line, and discovered that the mutant cells were unable to remove the activated T-cell receptor from the plasma membrane. This receptor protein is expressed on the surface of T cells, and is crucial for the control of their immunological functions. Once activated, it induces various signaling pathways that regulate the cell’s immune response, which must subsequently be turned off again at the appropriate time. “Unbalanced signaling can lead either to immune deficiencies like those observed in our patients, or cause autoimmune diseases,” says Klein.

Source: Read Full Article