Many men stopped getting screened for prostate cancer after a federal advisory committee said in 2008 that the tests weren’t helpful for those over 74. Then in 2012, it said the evidence supporting tests for younger men was weak too.

But new data suggests that guidance may have been a mistake.

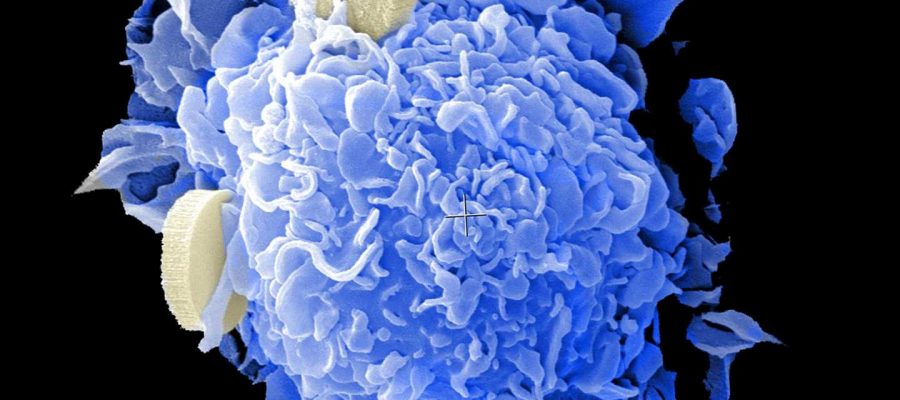

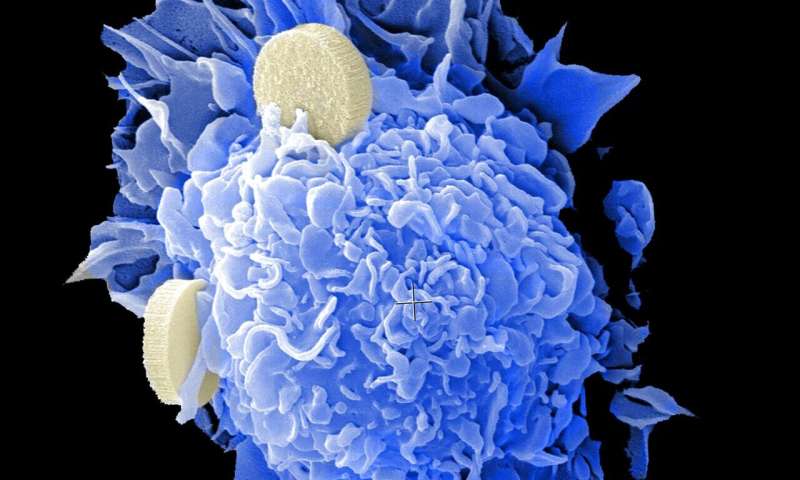

The number of men diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer has risen by more than 40% over the last decade, potentially because those cancers weren’t caught earlier with prostate-specific antigen, or PSA, screens.

It’s too soon to know whether those advanced tumors will be lethal, but early indications suggest they may be cutting lives short, said Dr. Richard Hoffman, who wrote a commentary accompanying the new research.

“What we learned is there’s a consequence” to reducing screening, said Hoffman, a professor of medicine at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City.

The panel that writes guidelines for cancer screening, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, changed course again in 2018, recommending that men discuss prostate screening with their doctor and make an individual decision based on their risks and fears. Hoffman said he supports that guidance.

PSA tests faced criticism because they identified a lot of cancers that were never going to cause harm, leading to treatments that did. Therapies routinely left men leaking urine and unable to get an erection.

“There are definite benefits and harms from screening. Men should be offered a chance to make a decision,” Hoffman said.

The most recent change in federal recommendations did a good job of reducing overtreatment, said Dr. Inderbir Gill, senior author on the new study. Today, the determination of who should get a PSA test is “far more nuanced,” said Gill, executive director at the University of South California Institute of Urology.

To avoid overtreatment today, men are categorized as low-, medium- or high-risk, using a PSA score, along with age, family history and other data.

The roughly 10% diagnosed at high risk are counseled to get immediate treatment, Hoffman said, while about half are offered what’s called “active surveillance,” which means continuing to track PSA levels and other measures to catch cancer if it starts to turn dangerous.

Active surveillance, Gill said, gives patients and doctors time to observe any cancer over time, consider options and come to a shared decision about treatment.

“Patients should not be scared that, ‘Oh my God, if I start this, I’ll end up on the operating table.’ Anything but,” he said.

H. Gilbert Welch, senior investigator in the Center for Surgery and Public Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said the urology community has done a good job acknowledging the flaws with PSA screening and addressing them.

“Overdiagnosis was such a huge problem for prostate cancer,” said Welch, who studies unnecessary treatments and diagnoses. “Screening always comes with harms.”

Some prostate cancers will never do harm while others are so aggressive that even early diagnosis will not prevent them from killing. Screening is intended to catch those tumors in the middle—where early diagnosis will make a life-saving difference—but it can be hard to reach such precision, Welch said.

Prostate cancer causes no symptoms until it has spread beyond the prostate.

Because prostate cancer is so slow-going, Welch said it’s still too soon to know whether the increase in advanced cancers referenced in the new study will eventually lead to additional deaths.

But reductions in screening occurred shortly before increases in diagnosing later-stage prostate cancer, which is harder to treat and more life-threatening, according to the new study, as well as other research from Europe.

In men 45 to 75 years old, the rate of advanced prostate cancer jumped 41% between 2010 and 2018, the last year data is available. For men 75 and up, the increase was 43%, according to the analysis of data from the annual Surveillance Epidemiology and End Result, which tracks more than a quarter of cancer cases nationwide.

The data included more than 800,000 patients with prostate cancer, 69% of whom were identified as non-Hispanic white men, 15% were non-Hispanic Black men and 9% were Hispanic men.

Diagnoses of advanced cancer had been falling in the early 2000s, particularly among older men. That trend reversed shortly after the recommendations for PSA screening were dropped or limited, according to the study.

The increase was most pronounced among white men, where diagnoses of advanced cancer increased from about 10 to 16 out of every 100,000 younger men over the study period and from 58 to 93 per 100,000 older men.

Among Black men, the rates jumped from about 29 to 40 per 100,000 younger men, and 97 to 126 in older men. Among younger Hispanic men, rates rose from 14 to 16 per 100,000 and among older Hispanic men from 62 to 90 per 100,000, the study found.

The database does not include information about which men received PSA screens and which didn’t, so it cannot determine that the lack of a PSA led to metastatic disease. But the timing of the rise suggests that the reduction in timing led to more advanced disease, said Dr. Mihir Desai, who helped lead the research.

“The rationale for screening is much more sophisticated” than it was a decade ago, wit Desai said. “That’s where the shared decision-making comes in.”

MRI, which is now available, can help decide which men should undergo biopsies to look for aggressive cancer, leading to less overtreatment, Desai said.

And recent treatment advances mean fewer men will suffer long-term consequences when they are treated, said another co-author, Dr. Giovanni Cacciamani.

Instead of removing the entire prostate every time cancer is detected, oftentimes, only one side of the prostate needs to come out, leaving most of the nerves and the sphincter untouched. In the fraction of men whose cancer recurs after focal treatment, the remainder of their prostate can still be targeted, Gill said.

The researchers said they hope the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force takes studies such as theirs into account when making recommendations.

“Most men who die of prostate cancer should have the opportunity of being detected and screened when they were potentially curable,” Desai said. “Given its slow biological progression, we feel many metastatic cancers could have been caught in a potentially curable stage.”

Source: Read Full Article