While intrauterine devices can be an effective, carefree way to protect yourself from pregnancy for up to 10 years, most medical procedures—and many birth control methods—carry a small risk of adverse effects. Tanai Smith, a 25-year-old student and mother from Baltimore, Maryland, explains how an IUD complication that plagues roughly 1 in 1,000 users led to the loss of her ovaries, uterus, and toes. (Click here for more information on birth control methods.)

When I slipped my left foot out of my sock, my toes were black, cold, and hard to the touch. Because the nerve endings there were already dead, I couldn’t feel a thing.

Although there was no sign of bleeding, my middle toe, I noticed, had fallen off into the fabric. Like a baby tooth, it had been loose. And yet, seeing it neatly detached from my body still totally freaked me out. Instead of screaming, I sprung into action, jumping up to grab a Ziploc bag and seal the toe inside.

When I called my doctor to explain what had happened, he told me to throw it away—there’d be no use for it now, he said. After all, in a few weeks’ time, a surgeon would remove the rest of the toes on my left foot and the tips of my right ones—all of which had begun to darken and die, too.

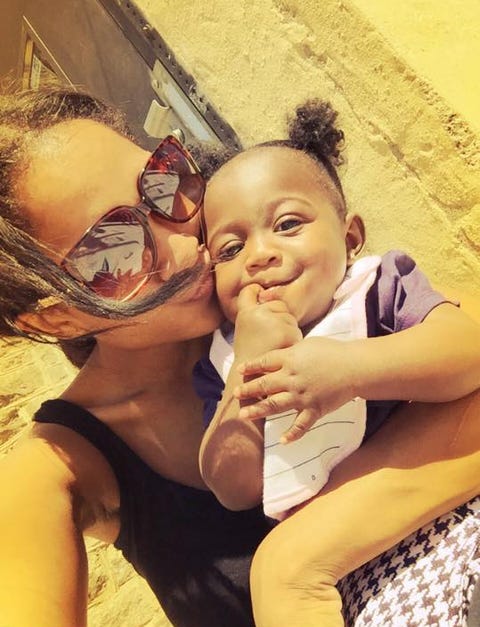

Tanai Smith

As a 25-year-old college student who works two day jobs, I didn’t expect this to be my story. It started after my daughter Morgan was born about three years ago. Although I wanted at least two more kids so Morgan could grow up with two siblings, just like I had, I wasn’t planning to have any more children with her father, who’s no longer in my life.

To keep me from getting pregnant for the time being, while I was at the hospital, my ob-gyn recommended a hormonal intrauterine device that’s designed to work for up to five years. Because it’s low maintenance and highly effective, it was the best option to prevent pregnancy, she told me, and because it’s low risk in terms of complications, I shouldn’t have any problems. I was young and healthy. I had no reason to think otherwise.

After doing a little research, I returned to my ob-gyn eight weeks later to have the T-shaped piece of plastic inserted into my uterus. The procedure went as planned, with just one complication: When trimming my IUD string, which is supposed to hang 1 to 2 inches long in the cervix so it can be easily located and removed, my doctor said she’d accidentally cut it too short. It didn’t seem like a big deal at the time.

My doctor reassured me that my cramping and constant headaches were normal and would soon subside.

Although some women experience cramping and backaches for three to six months after IUD insertion, typically, pain subsides within minutes, according to Planned Parenthood. Hormonal IUDs can sometimes trigger headaches, nausea, breast tenderness, mood changes, and ovarian cyst formation, according to The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

After a couple weeks, I felt perfectly fine. I didn’t give my IUD much thought after that, especially since my periods were normal and regular, and I didn’t feel any pain.

Fast-forward three years to this past October, when I went to a new ob-gyn for my annual checkup. (I only went to one who’d inserted my IUD during my pregnancy and postpartum period.) During my vaginal exam, she told me she couldn’t see my IUD. Although the devices sometimes can fall out, I knew for a fact that mine hadn’t.

.

I went to a radiologist later that day for an ultrasound scan of my stomach, cervix, and uterus. There was no evidence of the device, which confirmed it had gone missing. But because I had no symptoms, I wasn’t worried.

I was at work one day in November when suddenly, I felt like I’d been stabbed right below my belly button. The pain, which came and went, was totally different from period cramps and absolutely unbearable. It got so bad that I left work early and went straight to the emergency room.

At the hospital, I got an X-ray that told a very different story from my October ultrasound. My IUD was in there, alright: It was wedged into the wall of my stomach. My doctors didn’t say whether they’d ever seen this happen before.

On average, IUDs perforate or migrate outside the uterine cavity in fewer than 2 in 1000 users. Research suggests the position of your uterus, force used during IUD insertion, and getting an IUD soon after childbirth or while you’re breastfeeding can all amplify your risk, which may warrant surgery, according to Planned Parenthood.

When I showed the X-rays to my ob-gyn at an appointment two days later, the pain already had subsided. (It only lasted that one horrible day.) She referred me to a colleague who specializes in IUDs, and I saw him one week later.

I was told there were two possible reasons why the IUD might have migrated: Either it was put in too soon after childbirth, and the healing of my uterus pushed it up, or the tightening of my muscles during each cycle may gradually have pushed the device upward—but doctors weren’t exactly sure why it happened.

The specialist told me I’d definitely need surgery to remove the device, and I agreed. Although I felt perfectly healthy, with no symptoms, I wanted it out.

Courtesy of Tanai Smith

He expected to make one incision below my belly button and use a scope to extract the IUD in an outpatient procedure that would take about an hour. Because I’d be put under general anesthesia during the surgery and given painkillers after, he told me, I didn’t anticipate much pain or other side effects.

I was anxious when I went in to the hospital on December 13 — and not just because this would be my first operation. I had other things on my mind, like a school paper due that day. Thinking I’d be totally fine, I’d brought my laptop and textbooks to work from the recovery room.

When I woke up from the anesthesia, instead of one incision, I noticed I had three: One near my belly button and one on either side. The doctors told my mom the device had been hard to locate: During the four weeks that passed between my X-ray and procedure, it had migrated from my stomach to my liver and broken into four or five pieces, although I don’t know if this happened on its own or as a result of the surgery. (I don’t think a second X-ray right was done right before the procedure and I didn’t ask.) Ultimately, they were able to locate the device and remove all the pieces.

After the surgery, I was given pain medication that made my memory fuzzy and blunted discomfort: I barely remember leaving the hospital with my mom, and it wasn’t until I got home that the area began to really hurt. That night, I woke up vomiting—a side effect I hadn’t been warned about.

The next morning, severe pain was radiating from my abdomen, and the vaginal bleeding, which began at the hospital, had gotten heavier. Concerned, my mom called an ambulance.

In the emergency room, doctors agreed that I shouldn’t have been bleeding so heavily. They took an X-ray, then wheeled me back into the operating room.

Post surgery, I woke up in the intensive care unit with a breathing tube down my throat. My mom was by my side, encouraging me to stay calm.

Courtesy of Tanai Smith

I spent the next several weeks drifting in and out of sleep. It took a while for me to piece together and process what had happened during my second operation: The surgeon had removed both my ovaries and my uterus, which had blackened inside my body. I still don’t know why and whether my IUD or initial surgery were to blame. My doctors guessed my body was under stress going into the first surgery, during which I might have picked up some type of bacteria. They really didn’t give me any reason.

After the second surgery, I developed an infection known as sepsis from exposure to bacteria or stress from the surgery—my doctors couldn’t say. In response, my blood pressure dropped. My kidney functioning had been affected, so I was put on dialysis.

I later learned that I was given vasopressors, a kind of medication given to septic shock patients to raise the blood pressure by increasing blood flow to essential organs, even though it can lead to loss of feeling in the hands and feet. At the time, I didn’t know what was going on or what would happen. I was convinced I wouldn’t make it—that I would die.

“I was convinced I wouldn’t make it — that I would die.”

I spent Christmas and New Year’s Eve in the hospital thinking of my daughter, whom I hadn’t seen for weeks since I didn’t want her to see me connected to wires and tubes—I looked too scary.

Every time my doctors came in, they delivered bad news. It was so scary not knowing what would happen next. They would wake me up and ask whether I could feel my hands, which felt tingly, and feet, which grew numb. My doctors were alarmed and warned me that I may lose my limbs. Although I imagined what it would be like to have no hands and feet, I didn’t cry at the thought of it—I was in disbelief.

At the end of my third week in the hospital, sensation returned my hands while my toes began to blacken from necrosis, tissue death due to loss of blood flow. Even as my toes were turning black, I hoped I’d beat the odds.

On February 2, almost two months after my first surgery, I was finally discharged with a prognosis that hung over me for months: When I felt ready, I’d need to return for the removal of all the toes on my left foot and the tips of my right toes. I scheduled the procedure for May 2. I stayed in the hospital for a few days afterward, but there were no complications.

My situation is upsetting, but I’m thankful I didn’t lose my hands and all my feet, which would take a lot of adjusting. As it is, I’ve had to slow things down: Although I haven’t been able to return to school or part-time jobs at Target and Johns Hopkins Hospital, where I worked as a residential assistant, I can still fulfill my daughter’s basic needs and bring her to the park—even though it’s painful to walk, and I’m stuck on crutches for now.

Tanai Smith

I expected my amputations to bring me some sense of closure, but every day I think about what happened and wonder, why me? It’s always on my mind — I wish I knew what went wrong, so when my daughter asks why she has no brothers or sisters, I can explain.

Although what happened to me won’t happen to everyone, I hope other women will be careful when deciding how to prevent pregnancy. I don’t regret getting the IUD in the first place—I did my research—I just never heard of complications as severe as what I’ve experienced.

Until Tanai can return to work, she’s raising money to support her and her daughter via GoFundMe. Click here to donate.

From: Cosmopolitan US

Source: Read Full Article