Danielle Quintana, certified perioperative nurse and assistant clinical professor at the University of Houston College of Nursing, has conducted the first concept analysis on surgical conscience among perioperative nurses, those charged with overseeing surgical safety and sterile fields, or asepsis (the absence of bacteria, viruses and other organisms), inside hospital operating rooms.

Surgical conscience is defined as the moral obligation to perform those duties no matter the cost or consequence. It is a 360-degree awareness of all activities occurring within the perioperative environment and requires personnel to monitor their own practice as well as the practices of others to ensure patients are provided with safety and care.

“Acting upon one’s surgical conscience may not always be well-received by perioperative colleagues and may require the nurse to stand strong for what is right,” reports Quintana in the cover article of AORN Journal. “Regardless of the challenge presented, surgical conscience encompasses the belief that health care professionals have a responsibility to patients and to themselves to be consistent, accurate and safe. This duty or obligation should be performed with the highest level of commitment.”

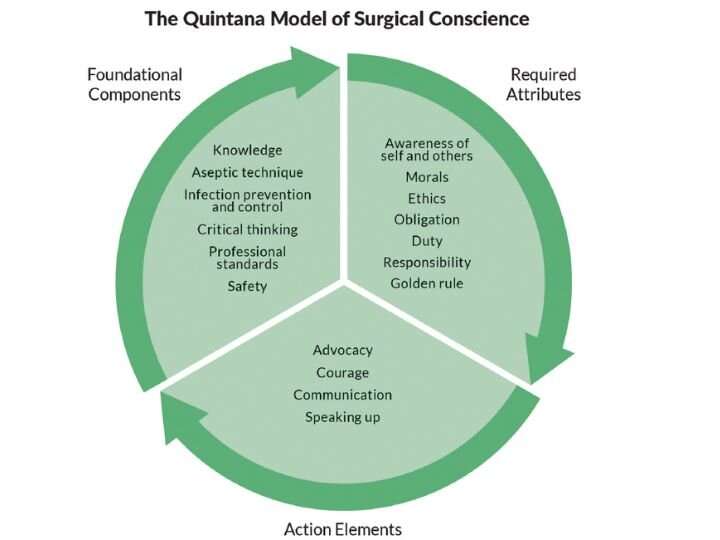

Quintana has also created a conceptual model representing surgical conscience to illustrate the use and context of the concept.

“Quintana’s work is inspiring as it leads to better patient outcomes, better communication with surgeons and the OR staff, and education of our students,” said Kathryn Tart, founding dean of the UH College of Nursing. “The Quintana Model of Surgical Conscience encapsulates the heart of what best practices should be for our patients, how we teach our students and collaborate with our surgeons and OR team.”

The perioperative environment is dynamic and complex, often requiring nurses to make difficult decisions under pressure and acts of surgical conscience may often cause delays. Examples include recognizing that a patient’s surgical site has not been correctly marked and waiting until the surgeon has properly identified the site before transporting the patient to the operating room; or, halting a procedure if a patient has a question regarding informed consent.

Despite years of training and courage on the frontlines, perioperative nurses face several possible reasons they may not feel empowered to demonstrate their moral courage and speak up, including a perceived hierarchy in the OR, a facility’s culture, navigating challenging personalities and a fear of retribution.

“Personnel should use their knowledge of sterile technique, attentively avoid and recognize breaks in technique, and immediately begin to mitigate breaks in technique when they occur,” said Quintana. In reviewing past studies, she found that nurses were also concerned about teamwork performance and that stress may have prevented them from exercising surgical conscience and thereby negatively affected surgical outcomes.

Little research exists on how surgical conscience is introduced, learned, improved or measured. Quintana’s analysis presents the current state of the science.

“This concept analysis provides a comprehensive definition of surgical conscience to guide the future research that is needed to reinforce surgical conscience and prevent conceptual dogma—a situation in which attributes of a concept lack the support of additional investigation but are still used and reinforced over time,” said Quintana. “The surgical conscience falls into several domains, including nursing, surgery, anesthesiology, surgical technology and interventional radiology.”

In the Quintana Model of Surgical Conscience, knowledge is the foundational basis of surgical conscience and includes the knowledge of professional standards and principles of aseptic technique, sterility and infection control.

Source: Read Full Article