Hospital admission is a worthwhile time to ask patients whether they usually have sufficient food at home, then connect them to community resources if necessary. That conclusion comes from a quality improvement project by Dr. Emily Gore, a recent graduate of the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, and colleagues. They describe their project in the Journal for Healthcare Quality (JHQ).

In primary care clinics and emergency rooms, nurses often ask patients about economic and social conditions that may be affecting their health, such as housing instability and intimate partner violence. A condition that’s less emphasized in those places—and even less so during hospital admissions—is food insecurity. That term refers to reduced quality, variety, or desirability of food, or inadequate access to food.

“Although our hospital serves a population with a high prevalence of food insecurity, no process previously existed to universally screen patients,” Gore and co-authors explain. To test whether they could improve that situation, they trained nurses in a 26-bed unit to add two items to their intake interview when patients were admitted to the hospital:

- Within the past 12 months, you were worried that your food would run out before you got the money to buy more

- Within the past 12 months, the food you bought just didn’t last and you didn’t have money to get more

Patients were asked to respond “never true,” “sometimes true,” or “often true.”

Impact of food insecurity

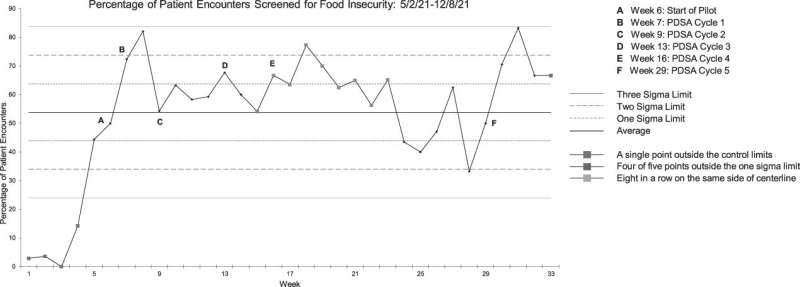

The quality improvement project began on June 7, 2021. Over the next 28 weeks, an average of 61% of patients were asked about food insecurity each week. In contrast, before the project started, only 2% of patients per week, on average, had been asked about food insecurity.

“[S]uccess was sustained despite challenges with nursing staff turnover and staff shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the authors note.

During the first 28 weeks of the project, 6% of patients answered “sometimes true” or “often true” to one or both questions, meaning they screened positive. Their nurse consulted a social worker, who gave the patients a list of community food resources.

“A reduction in food insecurity is expected to reduce healthcare costs and improve overall patient health, including cardiometabolic risk and [blood sugar] control,” Gore and her colleagues say. They are working now to incorporate screening for food insecurity across other units at their hospital. “[W]e also plan to connect patients to a hospital-based food pantry service—an effort that has demonstrated success at other institutions.”

Next steps to improve food insecurity

The food insecurity project is reported in a special issue of JHQ designed to highlight successful approaches to improving the health of underserved or marginalized populations. “[O]ur nation continues to underperform on [several quality and patient safety] measures,” according to the editors of the issue, Allyson G. Hall, Ph.D. and Michael J. Mugavero, MD, MHSc of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Source: Read Full Article