Starting in early 2020, COVID-19 wrought havoc in the lives of American society at all levels. Among groups most upended were first-year college students—young people at a critical point in their psychological development as they began to navigate lives on their own.

“For students going to college shortly after high school, it’s often the first time they’re living independently,” said Andrea Follmer Greenhoot, professor of psychology at the University of Kansas. “They’re making more decisions for themselves. They’re exploring identity and career-related roles. They’re developing new relationships. All these transitions involve developing a sense of who they are and where they want to be going. Those were disrupted by the shutdown in April 2020—everything came to a screeching halt.”

Follmer Greenhoot, who also serves as director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and Gautt Teaching Scholar at KU, is co-author of two new scholarly papers based on a longitudinal study of 629 first-year college students at four U.S. universities that began just weeks after the initial lockdown and continued with three more check-ins over the subsequent year.

Participants reported on their mental health, academic adjustment, identity development and COVID-19 stressors. They also shared personal narratives about their experiences during the pandemic.

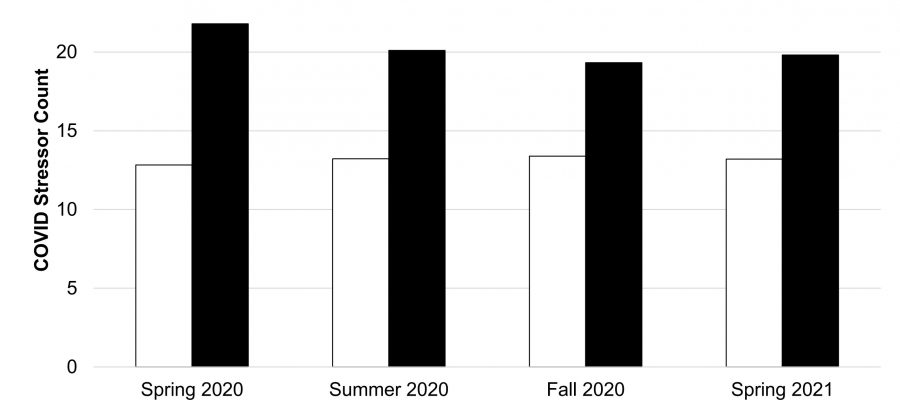

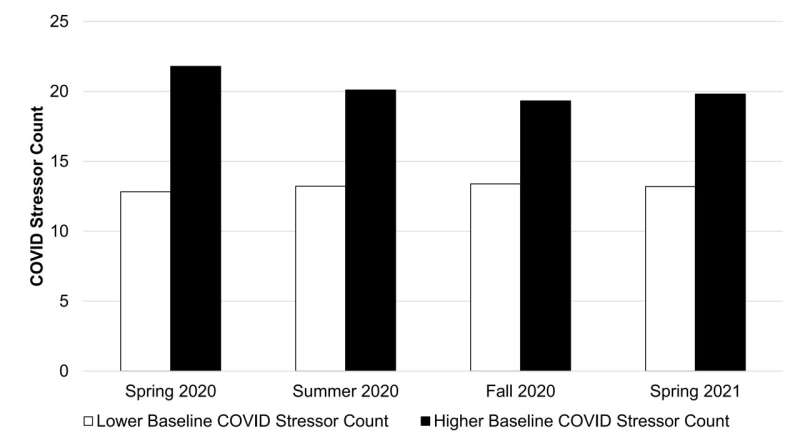

The first paper, published in Emerging Adulthood, finds the pandemic negatively affected student mental health, development of identity and academic resilience when compared with pre-COVID data. Further, Follmer Greenhoot and her colleagues found “these alterations persisted and, in some cases, worsened as the pandemic wore on; and patterns of change were often worse for students indicating more baseline COVID-related stressors.”

“This paper focused on trajectories of adjustment over the year after the pandemic began,” Follmer Greenhoot said. “These students really struggled. While there’s been a lot of work looking at the impact of the pandemic on mental health in student populations, probably the most important takeaway from this study is that it’s also been a developmental disruption. The pandemic has really derailed some important developmental tasks that are typical for emerging adults in college.”

According to a summary of the research effort, students’ narratives frequently referenced themes such as:

- Academic distress; lack of motivation

- Loss of efficacy and academic confidence

- Loss of autonomy/control

- Social disruption, loneliness

- Goal and activity disruption; loss of formative experiences, stalled decision-making and identity formation

Samples from students’ stories illuminate these developmental disruptions and the mental health challenges posed by COVID-19.

“I find myself with absolutely no motivation, constantly finding the easiest way to complete assignments and overall learning hardly anything,” said one participant.

“… is this really the career I want? The coronavirus took away every future life I thought I knew… This is the most pivotal and influential portion of my college career, and I am going to miss out on a lot of the experiences that will define my education,” wrote another student.

Follmer Greenhoot said the research should inform mental health providers and parents. As director of KU’s Center for Teaching Excellence, she has particular interest in the research’s implications for educators and staff who interact with students in higher education.

“We need to recognize that in addition to the fact that students are stressed and struggling with mental health, it’s also the case that some of these developmental experiences haven’t happened for them,” she said. “That changes who we get in our classroom and on campus and what they need out of the college experience.”

Follmer Greenhoot’s collaborators include Monisha Pasupathi and Cecilia Wainryb of the University of Utah; Jordan Booker and Mikayla Ell of the University of Missouri; Kate McLean of Western Washington University; and Robyn Fivush of Emory University.

The team discovered positive results as well. In a second paper appearing the peer-reviewed journal Psychological Science, the team analyzed student narratives, comparing them with data collected over the subsequent year. Follmer Greenhoot said the researchers discovered many of these college freshmen were able to make sense of their own COVID-19 experiences in ways that gave them resilience.

Most notably, first-year college students who mentioned personal growth when writing stories about their COVID-19 experience at the pandemic’s outset tended to be more resilient to its hardships. References to growth address new knowledge, reasoning, attitudes, behaviors, or personal strengths and resources as a result of the lived event, according to Follmer Greenhoot.

“The main finding we highlight in the Psychological Science paper was the power of students referencing growth in their narratives about the pandemic at the initial time point,” she said. “Students whose narratives in April of 2020 tended to reference growth from events they were exposed to showed greater resilience across a whole range of measures. We found those references to growth were a significant predictor of how they were doing a year later.”

This, in spite of participants experiencing more sources of COVID-related stress than researchers anticipated.

“We were interested in the relationship between their narratives about the experience and these measures of adjustment,” said Follmer Greenhoot. “We also gathered information about the types of COVID-related stressors they were exposed to overall, like not being able to see loved ones, a family member losing their job, someone in their life dying. We were surprised at how many stressors students were exposed to—somewhere between 15 and 17 distinct stressors related to COVID on average at each time point.”

But the KU researcher said those students referencing growth in their narratives tended to fare better than students not citing personal growth, even if they experienced more numerous or more severe COVID stressors.

“There was quite a bit of variability, and one might normally think the number of stressors or the level of stress they were exposed to would be a big predictor of their adjustment, both concurrently and long-term,” Follmer Greenhoot said.

“That was the case, except when we considered the characteristics of their narratives about those stressful experiences. It turns out it’s the way they’re constructing their narratives about the experience that really provides insight and prediction into their adjustment. That was more important—it washed out the impact of the actual stress levels they were experiencing. It speaks to the importance of sense-making, how we process our experiences and how we come to react to them over time.”

More information:

Monisha Pasupathi et al, College, Interrupted: Profiles in First-Year College Students Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic Across One Year, Emerging Adulthood (2022). DOI: 10.1177/21676968221119945

Jordan A. Booker et al, Early Impacts of College, Interrupted: Considering First-Year Students’ Narratives About COVID and Reports of Adjustment During College Shutdowns, Psychological Science (2022). DOI: 10.1177/09567976221108941

Journal information:

Psychological Science

Source: Read Full Article