Andy Weinberg’s feet looked like they were dunked in lava. His toes were ashen black and blue with frostbite. The pictures of his feet on his phone didn’t seem real. But with Weinberg, one of the founders of the Endurance Society and former co-founder and partner in the Spartan empire, this wasn’t a joke. An injury like that was bound to happen. What’s remarkable is it took this long.

Weinberg got frostbite during a weekend in the Adirondack Mountains with a crew of 15 people he led on a 48-hour hike through snow- and ice-covered trails in sub-zero temperatures for fun. It was the Endurance Society’s annual Extremus event, a weekend-long hike in the middle of the winter over some of the Northeast’s toughest and tallest peaks.

At one point during this year’s version, Weinberg had to stand out in the open, no longer under the cover of trees that blocked the life-threatening wind chill, and directed people over cliffs along the Great Range. The team hiked 20-plus miles over eight peaks. It was one of the coldest weekends of the year and, according to Weinberg, no one except him and a friend, also named Andy, got injured. The frostbite looked horrible, but Weinberg laughed it off when he showed me the photos. He gets to keep his toes and the experience was worth the pain and injury, even if his wife Sloan, and people like me, don’t understand it.

“I was stuck out there,” Weinberg says. “[Sloan] doesn’t understand the whole backstory or why you’d risk these things. We were very prepared. I didn’t plan on getting frostbite; shit happens.”

Weinberg grew up an adrenaline junkie. Raised in Peoria, Illinois, he’d ride his bike as far from home as he could and test the limits of his ability to get back in time. He’s ridden on a solo bike ride from Illinois to Vermont and has hiked countless mountains, favoring more hostile winter conditions.

“I don’t surf the big waves, but I get it. I understand why those guys do it,” Weinberg says. “I don’t ride a motorcycle around a track, but I totally understand that adrenaline junkie has that fix. Mine is more of an endurance and adventure fix.”

“I didn’t plan on getting frostbite; shit happens.”

Growing up, Weinberg struggled with attention deficit disorder (ADD). To combat his energy, his mother signed him up for swimming. The pool — the exercise and the routine of training — kept him focused, for the most part. He joined a club team and earned a college scholarship to Missouri State University in southwest Missouri. There, Weinberg met Sloan and started hiking the Ozark Mountains instead of going home during school breaks. The wilderness and the exercise had the same effect as swimming.

After college, Weinberg moved to his hometown and became a high school gym teacher and swim coach. He started racing in Iron Man and other endurance events. Weinberg eventually got tired of traveling to bigger cities and out of state to race, so he started his own in central Illinois. His first race as organizer was the McNaughton 50 mile run in Pekin, Illinois. That seemed fine, if not repetitive, until he met Joe De Sena.

The pair met at a race and discussed how endurance races were predictable. The limits and distances were set, and the only thing that changed was the scenery. They devised the famed Death Race, which challenged racers mentally as much as it did physically. No one knew when the race was over, or what was coming next. You might have to find your clothes in a snowbank after a bikram yoga session or solve a puzzle or work with your fellow racers to build a set of stairs up a mountain.

The Death Race morphed into the Spartan obstacle race empire. In 2007, Weinberg took a job coaching swim at Middlebury College and uprooted his family to Pittsfield, Vermont, where De Sena lived, and where they planned to host the Death Race (the rest of the family moved to Vermont officially in 2008). Before moving, Weinberg decided to ride his bike from Peoria to Middlebury, with a detour through Canada and the Adirondack Mountains for an extra challenge.

“We were having a barbecue at our house with a bunch of friends — drinking, hanging out — and they go, ‘Are you stupid? You can’t ride to Vermont.’ So there was this doubt in this room and I thought, I can. I ride my bike all the time anyway,” Weinberg says. “I had just finished training for a double Iron Man, you know the Iron Man triathlon, I had just done a double Ironman, so I was in pretty good shape.”

Weinberg made it to Vermont in eight days. He spent a few nights sleeping on the side of the road and was nearly arrested in upstate New York. He cried riding up the Adirondacks, the weight of his bike and the sudden drop in productivity causing him to rethink his plan. In the end, he made it to Vermont with time to spare and a story to tell.

Weinberg and DeSena’s relationship eventually disintegrated, and Weinberg left Spartan after a lengthy legal battle. After, Weinberg and his friend Jack Carey, whom he met through the Death Race, started the Endurance Society with the hope of creating more intimate and challenging events. Their first event was a hike over two of Vermont’s tallest peaks, Mount Mansfield and Camel’s Hump. The weather was brutal and the hike was called off after 36 hours, miles short of their final destination. It didn’t deter the pair. Instead, they created more elaborate events: a series of snowshoe races; a ski race up a mountain; and the ultra-secretive and private Sine Nomine event, where participants are sworn to secrecy and nothing save mandatory gear, food, and drinks are allowed.

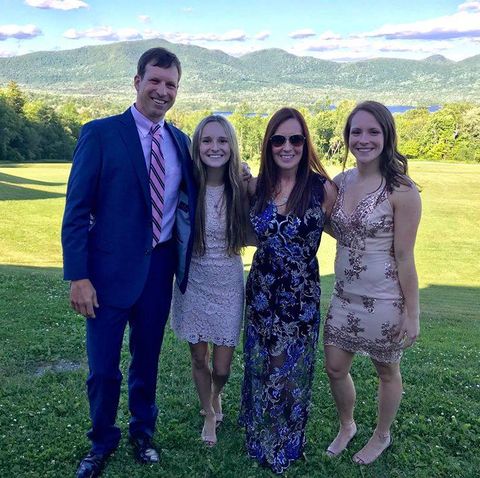

The Endurance Society has grown in the four years since it launched, bringing on corporate sponsorships like Gatorade and Rockstar Energy Drinks. Weinberg, who now teaches at Castleton College and lives under the shadow of Killington Mountain, is at a crossroads. He has a burgeoning company that keeps him busy with logistics, safety, marketing, and running events across Vermont and into Canada (Carey is no longer involved). He’s also teaching, volunteering with the Special Olympics, and raising two daughters, Grace and Jade, with his wife. Weinberg knows there’s more potential for the Endurance Society, but he fears the corporate element creeping in. He saw how Spartan went from a small, friends-and-family-oriented company to a global juggernaut with investors and a network television show.

Weinberg stood in the living room of his new home in Mendon, Vermont, and tells me to look out the large windows towards one of Vermont’s many beautiful mountain ranges. A few year ago, this spot was nothing but trees. There wasn’t a road, never mind a house. He did this with Sloan, and now he’s doing it with me now. He saw something here, a vision of a future.

In October, the house was finished. It’s powered by solar power and heated almost entirely by wood in the stove that Weinberg and a friend installed in the living room. But, like anything with Weinberg, a challenge was involved. The difficulties of building a home on an uninhabited side of a mountain wasn’t enough. No, he felt compelled to chop and split the more than 15 cords of hardwood logs left behind after construction finished. He needed to finish before winter, something the contractors told him couldn’t be done. So, he spent days and nights, sometimes with the help of friends, splitting wood, one log at a time until he’d done the impossible.

Source: Read Full Article