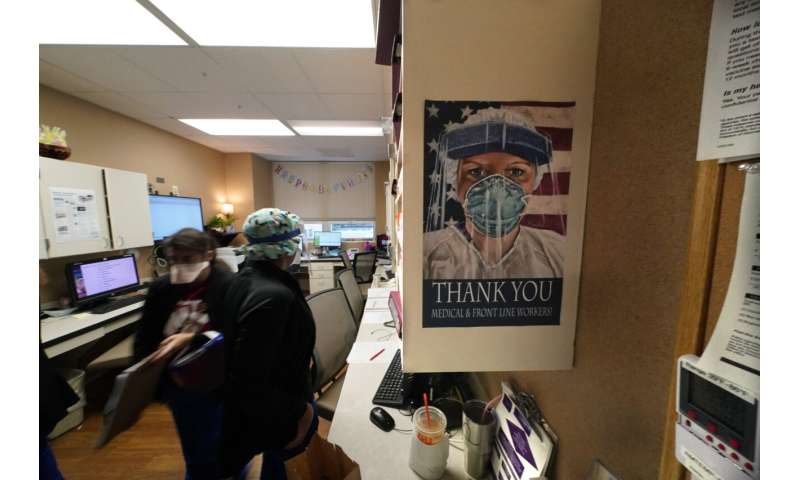

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a nurse staffing crisis that is forcing many U.S. hospitals to pay top dollar to get the help they need to handle the crush of patients this summer.

The problem, health leaders say, is twofold: Nurses are quitting or retiring, exhausted or demoralized by the crisis. And many are leaving for lucrative temporary jobs with traveling-nurse agencies that can pay $5,000 or more a week.

It’s gotten to the point where doctors are saying, “Maybe I should quit being a doctor and go be a nurse,” said Dr. Phillip Coule, chief medical officer at Georgia’s Augusta University Medical Center, which has on occasion seen 20 to 30 resignations in a week from nurses taking traveling jobs.

“And then we have to pay premium rates to get staff from another state to come to our state,” Coule said.

The average pay for a traveling nurse has soared from roughly $1,000 to $2,000 per week before the pandemic to $3,000 to $5,000 now, said Sophia Morris, a vice president at San Diego-based health care staffing firm Aya Healthcare. She said Aya has 48,000 openings for traveling nurses to fill.

At competitor SimpliFi, President James Quick said the hospitals his company works with are seeing unprecedented levels of vacancies.

“Small to medium-sized hospitals generally have dozens of full-time openings, and the large health systems have hundreds of full-time openings,” he said.

The explosion in pay has made it hard on hospitals without deep enough pockets.

Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly lamented recently that the state’s hospitals risk being outbid for nurses by other states that pay a “fortune.” She said Wednesday that several hospitals, including one in Topeka, had open beds but no nurses to staff them.

In Kansas City, Missouri, Truman Medical Centers has lost about 10 nurses to travel jobs in recent days and is looking for travelers to replace them, said CEO Charlie Shields.

He said it is hard to compete with the travel agencies, which are charging hospitals $165 to $170 an hour per nurse. He said the agencies take a big cut of that, but he estimated that nurses are still clearing $70 to $90 an hour, which is two to three times what the hospital pays its staff nurses.

“I think clearly people are taking advantage of the demand that is out there,” Shields said. “I hate to use `gouged’ as a description, but we are clearly paying a premium and allowing people to have fairly high profit margins.”

In Texas, more than 6,000 travel nurses have flooded the state to help with the surge through a state-supported program. But on the same day that 19 of them went to work at a hospital in the northern part of the state, 20 other nurses at the same place gave notice that they would be leaving for a traveling contract, said Carrie Kroll, a vice president at the Texas Hospital Association.

“The nurses who haven’t left, who have stayed with their facilities, they are seeing these other people come in now who are making more money. It provides a tense working environment,” Kroll said.

The pandemic was in its early stages when Kim Davis, 36, decided to quit her job at an Arkansas hospital and become a travel nurse. She said she has roughly doubled her income in the 14 months that she has been treating patients in intensive care units in Phoenix; San Bernardino, California; and Tampa, Florida.

“Since I’ve been traveling, I’ve paid off all my debt. I paid off about $50,000 in student loans,” she said.

Davis said many of her colleagues are following the same path.

“They’re leaving to go travel because why would you do the same job for half the pay?” she said. “If they’re going to risk their lives, they should be compensated.”

Health leaders say nurses are bone-tired and frustrated from being asked to work overtime, from getting screamed at and second-guessed by members of the community, and from dealing with people who chose not to get vaccinated or wear a mask.

“Imagine going to work every day and working the hardest that you have worked and stepping out of work and what you see every day is denied in the public,” said Julie Hoff, chief nurse executive at OU Health in Oklahoma. “The death that you see every day is not honored or recognized.”

Patricia Pittman, director of the Fitzhugh Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity at George Washington University, said many nurses still harbor resentment toward their employers from the early stages of the pandemic, in part from being forced to work without adequate protective gear.

Source: Read Full Article