As a child I was fascinated by the Numbskulls cartoon strip that was originally in the Beezer comic. You may remember seeing the inside of the head of “Our Man” divided into compartments and run by smaller men with names such as Brainy and Cruncher. It was seductively simple to think that our mental and bodily processes were controlled by a handful of little men, each with their own areas and specific jobs to carry out.

Of course it wasn’t long before I was faced with the dilemma of what was controlling the smaller characters’ actions. Was there an infinite number of little men, each inside the head of the last, controlling smaller and smaller versions of themselves in a never-ending Escher-like chain? I didn’t realise at the time that the Numbskulls cartoon was perhaps my first encounter with the homunculus and may have triggered my lifelong fascination with the workings of the human mind and body.

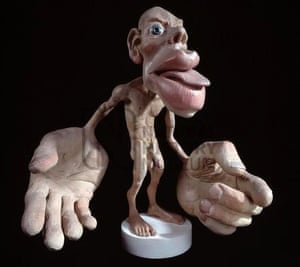

The term homunculus is Latin for “little man” and is used to describe a fully-formed miniature representation of a male human being. As a concept it has been used for centuries in preformationist, alchemic and fictional writing. Today, however, it is more often used in the field of neuroscience. An internet search using the term homunculus will immediately reveal images of a rather grotesque squat figure with grossly enlarged hands, face and to a lesser extent feet and genitals. You may spot a likeness to Peter Jackson’s interpretation of Gollum in the magnificent Lord of the Rings and Hobbit trilogies.

The most common homunculus model is a 3D representation of the amount of nerve space our various body parts take up in the regions of our brains devoted to feeling. The reason for the distorted proportions you see is that they depict areas that are provided with more information from certain parts of our body when compared to others. For instance, our hands are designed to manipulate fine objects and recognise shapes, important activities for everyday life which require a high concentration of nerve endings. Other areas such as our shoulder blades or backs of our knees don’t need to provide such detail. There are other homunculi in the brain such as those used to depict areas of nerves devoted to moving which will show some differences to the feeling one. The female version will obviously be slightly different too.

The homunculus is also used in 2D form to depict how our body parts are distributed in location over the surface of our brains. Images reveal a dismembered Gollum draped over the brain, again with slight variations between the feeling and movement areas, and between sexes. As you can see, Gollum isn’t running around our skulls eating live fish, biting fingers off and generally causing havoc, but is safely pinned down to the surface of our brains.

The fascinating thing about this homunculus, which is a topographical representation of the areas of the brain dedicated to feeling, is that it is constantly changing in response to our environment and how we interact with it. When we perform any series of movements there are a variety of nerve endings around our bodies that pick up this activity and relay the information via nerves to the sensory areas of our brain, a process known as proprioception. This is how we know that the movements we make match those that we had intended.

At the same time we also gather information from other types of nerve endings like touch and special senses such as vision to augment this. Like most physical processes, the more we use them the stronger or more efficient they become. The more often we perform varied and novel activities with our whole bodies, the stronger our sense of ourselves is defined in our brains.

We are now beginning to understand that general exercise and whole body movement is as effective as specific targeted exercise in recovery from chronic musculoskeletal conditions such as lower back pain. Studies such as the one performed at the Athens School of Healthcare Professions and published in 2005 showed that general exercise was just as effective as specific stabilisation exercises in improving back strength in patients with recurrent lower back pain. They concluded that improvements were most likely down to the changes in input from sensory nerves to the brain. In fact, overemphasis on training and tensioning back and abdominal muscles may make things worse, as discussed in an article titled The Myth of Core Stability published in 2010. However, there are times when specific prescribed exercises are vital, such as in recovery from an accident or stroke.

There is a growing body of evidence that suggests that when we neglect areas of our bodies through injury and fear of movement or simple inactivity, a person’s homuncular representation quickly begins to change. A 2013 study published in the Clinical Journal of Pain showed that subjects with chronic lower back pain were less able to detect sensory stimulation applied to their backs compared to pain free subjects. The authors concluded that it was plausible that this altered self-perception was a kind of faulty response to the pain, and could contribute to its persistence.

I first came across this idea of homuncular “smudging” in an invaluable book titled The Sensitive Nervous System by physiotherapist and educator David Butler, along with the suggestion that performing non-threatening body movements in a relaxing environment helps ‘refresh’ the homunculus and can play an important part in the recovery process from chronic pain.

This internalised picture of ourselves is so responsive to changing input that it can even incorporate an artificial limb in no time at all. The famous rubber hand illusion is a case in point.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=sxwn1w7MJvk%3Fwmode%3Dopaque%26feature%3Doembed

In this repeatable experiment, subjects are shown a rubber hand in place of where one of their own hands would normally be. The rubber hand is repeatedly stroked in synchrony with their own unseen hand until they start to perceive the rubber hand as their own, in other words it becomes incorporated into their homunculus.

In specialist areas of human movement, such as playing musical instruments, the homunculus can become developed in particular areas. An article in Science 1995 showed string instrument players to have a larger homunculus area for their string (usually left-hand) fingers as they required a higher level of fine motor skills. Another similar interesting study on Braille readers published in Brain in 1993 showed increased homuncular representation in their reading fingers (right hand) compared to their left and to non Braille-reading subjects.

Sadly the converse is also true if we spend a large amount of time sitting and performing repetitive tasks, or worse none at all. Our brains are use it or lose it organs just like our muscles and will respond to both increased, reduced, or absent stimulus. In fact if we are sedentary or perform repetitive tasks that have a negative impact, our brains will adapt to reinforce those patterns even though it may not do us any good.

Much has been written about the benefits of exercise and a lot of what has been publicly understood relates to strength and cardiovascular fitness, which are of course important. However, the effects on the function of the brain are just as important. A recent analysis published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine on the effects of exercise on the brain showed that executive functions, those such as decision making, planning and working memory were all significantly improved in children, adolescents and young adults after physical exercise.

Of course, refreshing your homunculus is just one good reason to get outside and engage in some physical activity. You might do it to be sociable, to tighten up family bonds, or to get a boost of vitamin D stimulating sunlight. But arguably the brain effects of regular physical activity are of equal importance.

Interested in finding out more about how you can live better? Take a look at this month’s Live Better Challenge here.

The Live Better Challenge is funded by Unilever; its focus is sustainable living. All content is editorially independent except for pieces labelled advertisement feature. Find out more here.

Source: Read Full Article